Boys are Builders: it’s time for the culture to “affirm” that

Saint Colum, Blessed Sebastian, and an unorthodox way to teach anti-communism

Since our culture is in the business of “affirming,” let’s go ahead and affirm the reality of boyhood. Boys need exactly the opposite of what is being provided in the government school system: they need time outside, yet they are confined to desks for many hours; they need a high protein, low sugar diet, yet they are fed highly refined and processed foods for lunch; they need lots of play with other boys, yet they are forced into co-ed environments designed for girls; they need masculine examples and heroes yet effeminacy is the norm; they need competition, yet everyone is declared a “winner.”

How to bring back a healthy culture of masculinity in which boys can thrive? First, give them playtime, but also give them books that affirm their boyish desires to build and do battle. I’ll review two such books that do the former here: Blessed Sebastian and the Oxen and Saint Colum and the Crane, both by Eva K. Betz.

Childhood is about building up the right kind of imagination: one that delights in the good, true, and beautiful. Don’t expect a child who is fed almost exclusively on a diet of junk such as Love you Forever, Where the Wild Things Are, and Llama Llama books to delight in the stories of the saints and adventures of Billy and Blaze. Two different types of imagination are being cultivated.

Don’t get me wrong, reading any of these books on occasion is not going to kill your kid’s imagination or do irreparable harm. It’s the totality of it. What dominates the bookshelf? What types of books do you grab in the evening before bed? And more importantly, what books does your child grab on his own? This will be a pretty good indicator of the type of imagination that is being cultivated.

In a culture that despises boys, it is important to “be intentional,” in post-modern parlance, about raising boys who will be boys—and not just boys but saints. Good literature plays a significant role in forming young imaginations, and putting before little ones models toward which they want to aspire. Blessed Sebastian and Saint Colum are great little books for boys (and also girls!) because they tell engaging tales of men who built things, and specifically male saints who built in order to give glory to God.

What’s also great about these books, which are part of the “Easy Reading Books of Saints and Friendly Beasts” series published by Neumann Press (an imprint of TAN Books) is that they tell the stories of two paragons of masculinity who each form a special bond with a particular animal. Sebastian and Colum are no effeminate “animal lovers” but men whose love of God is so profound that they develop a supernatural connection with an animal member of His creation. This bond with an animal illustrates and elevates their earthly work, acting as a sign of God’s grace.

Strictly verboten in the mainstream culture, these two books tell the stories of saints who brought the word of God to a backward people: Sebastian to the natives in Mexico and Colum to the Irish pagans. At the same time as these two men brought the word of God, they also brought material improvements.

“The more Sebastian traveled around in Mexico, the better he liked it. And the better he came to know the people, the more he loved them. They were good and kind, and very, very hard-working. Sebastian was eager to tell them about God and His Mother. He wanted, too, to make their lives a little easier.”

Sebastian, after living among the native peoples for some time, observed that they “carried their loads in bundles on their backs, and by the time the poor, tired travelers reached the market the fruits were often bruised and the vegetables not very fresh.” He wanted to improve their lot, and so he explained that if they built a road to the city, they could transport their goods to market much quicker and more easily. Although he did not know much about building roads, Sebastian nonetheless set out to clear the path, fell tress, roll away large rocks, and pave the muddy path with rocks and stones.

The road was so helpful that Sebastian decided another should be built from the mines to the shore.

“And when that was done, he built another, and another, and another. He never took any pay for the work. He loved the Mexican people, and was happy to be able to help them in this way. They were growing to love him, too. They loved him because he made their work easier; but they loved him even more because he was always ready to tell them about Jesus and His Mother.”

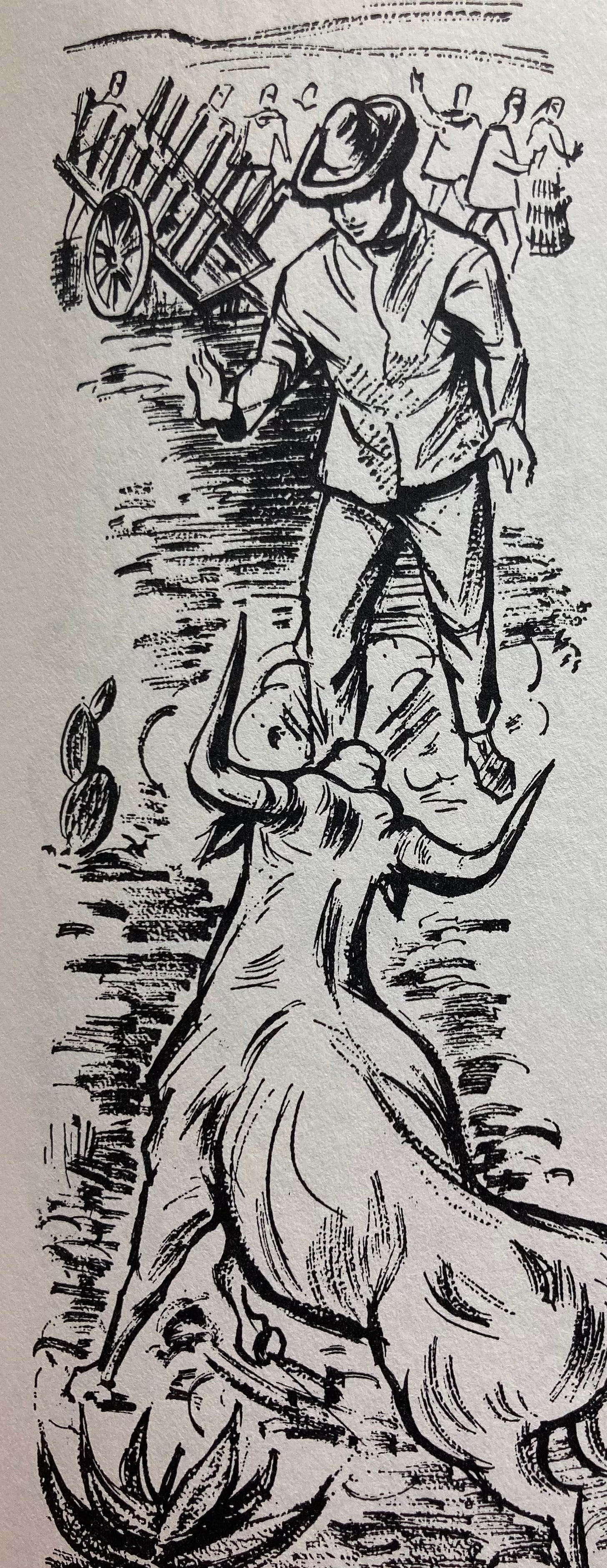

As Sebastian lived among this people, he continued to find ways to improve their lives. He noticed that their method of farming had not changed in thousands of years, so he introduced the plow. When he saw that they struggled to carry their large harvests to market, he introduced the wagon. Then he brought in donkeys to pull the wagons. Then he introduced a much larger wagon, which would require a much larger beast of burden: oxen.

“When the village people learned what Sebastian was planning to do, they grew very frightened. Oxen were big, powerful animals whom very few people dared to go near.” The people prayed to the Virgin and to St. Joseph to protect Sebastian when he went to break the oxen.

The oxen that Sebastian tames are also reflections of Sebastian himself, and show the potential of all boys: that they can use their strength to create. Just as oxen have the potential to destroy, they also, under the care of Sebastian, can use their strength to build. Boys today are only taught about their potential to destroy, but they ought to be shown that they have great potential to use their strength to build. Just as Sebastian breaks in the oxen, fathers can break in their boys (I watch that ongoing process here everyday). Of course, God the Father, is the ultimate tamer. “There are rules for plowing a field,” Sebastian told his Mexican friends, “and rules for getting to Heaven. You must learn them both, and obey them.”

This little title is, surprisingly, a good way to combat any Marxist tendencies your older high schooler might show! Not that this would happen to you, dear reader, but it’s almost an inevitability that you’ll have to have “the talk” about communism sooner or later. I actually found myself thinking about how reading this book with a high schooler or even college-aged child could open up a great conversation about the flaws in Marxism. For Marx and the socialists are philosophical materialists, meaning that they (ostensibly) do not believe in the reality of the spiritual world (in a sense, though, they do because Marxism is predicated on a kind of abstract, metaphysical “liberation” that is supposed to follow the economic transition to socialism/communism). Moreover, communists believe that altering our system of economic exchange will fundamentally alter material conditions, which in turn determine everything else about life from the political system to philosophical and religious beliefs.

If instead of Sebastian, a member of the Soviet politbureau (or the winner of the Democratic primary in New York City, Zohran Mamdani) came to “improve” the lives of the natives, he would have forcibly collectivized them onto a farm that would have seen a precipitous drop in yield and productivity instantaneously. The people, forced to give up their crop to the communist authorities for redistribution, would have had almost no incentive to work. An already low standard of living would, under communist “stewardship,” drop further. Yet this would all take place under the auspices of material improvement.

Sebastian, on the other hand, came not with the express intention of improving the material lot of the natives, but to improve their lives spiritually. Yet because he lived among them, observed their concrete ways of life, and loved them, he wanted to ease their earthly burden. He saw a better way of doing things, and knew that he could help to make improvements that would benefit everyone. Still, this mission was secondary to his first goal, which was to bring the Word of God to the people.

The beauty of this story is Sebastian’s desire to build, which manifests spiritually and materially. We are spiritual beings inhabiting a material world. Sebastian illustrates this. The story of Sebastian and the Oxen gives aesthetic expression to this truth in a compelling way. Young children need not understand this philosophical articulation. They will pick up on its truth aesthetically. The image—the symbol—strikes deep. It leaves an impression on the imagination.

For the high-schooler wondering what’s so wrong with Mamdani’s Afford to Live & Afford to Dream™ ideal, it should be pointed out that the ideologue’s desire to improve the material lot of a group of people in the abstract (that is, not thinking about particular circumstances), is doomed to fail because it cannot address particular needs. Sebastian saw that a road would help brings goods to market faster, so he built a road. Mamdani and the millions of other socialist dreamers are looking toward the abstract goal of “material improvement” without considering the specifics of what is needing improvement.

The Catholic missionaries, on the other hand, began with the concrete and specific. This people needs clean water. This other people needs roads. This people needs education.

And speaking of education, that is exactly what Saint Colum helped to spread throughout Ireland. Like Sebastian, Colum was a builder. And while he was at it, his kindly, Godly heart attracted the friendship of a crane.

Colum built a monastery, which grew very large. Then he built another monastery, and another and another and another. Every monastery he built grew and grew. And he considered the physical space of the monastery as part of his spiritual mission. When building the first monastery on a plot of land in a mountain that he was gifted, Colum worked so as to retain as many trees as possible in order to preserve the life of the trees and the natural landscape. It is possible to be an “environmentalist” motivated not by abstractions but by the concrete desire to preserve God’s beautiful creation while at the same time working to spread the Gospel.

Colum, I want to add, wrestled with an irascibility that causes him, at one point in the story, to foment war. This part of the story many boys could probably relate to. It makes the tale all the more wonderful because it illustrates that Colum, although a saint, had weaknesses, even to the point of causing enormous suffering. Yet he takes his penance like a man.

In sum, these two little volumes are great reading for boys, putting before their imaginations worthy heroes. The concreteness of the stories and the interesting details of the saints’ lives make them great additions to the home library.