The enormously popular Llama llama books by Anna Dewdney have all been New York Times bestsellers and have been used in literacy programs, including at the Library of Congress, adapted into stage plays and musical performances, and are a “Netflix original series.” When a subscriber recommended that I write about this series, it was a no-brainer.

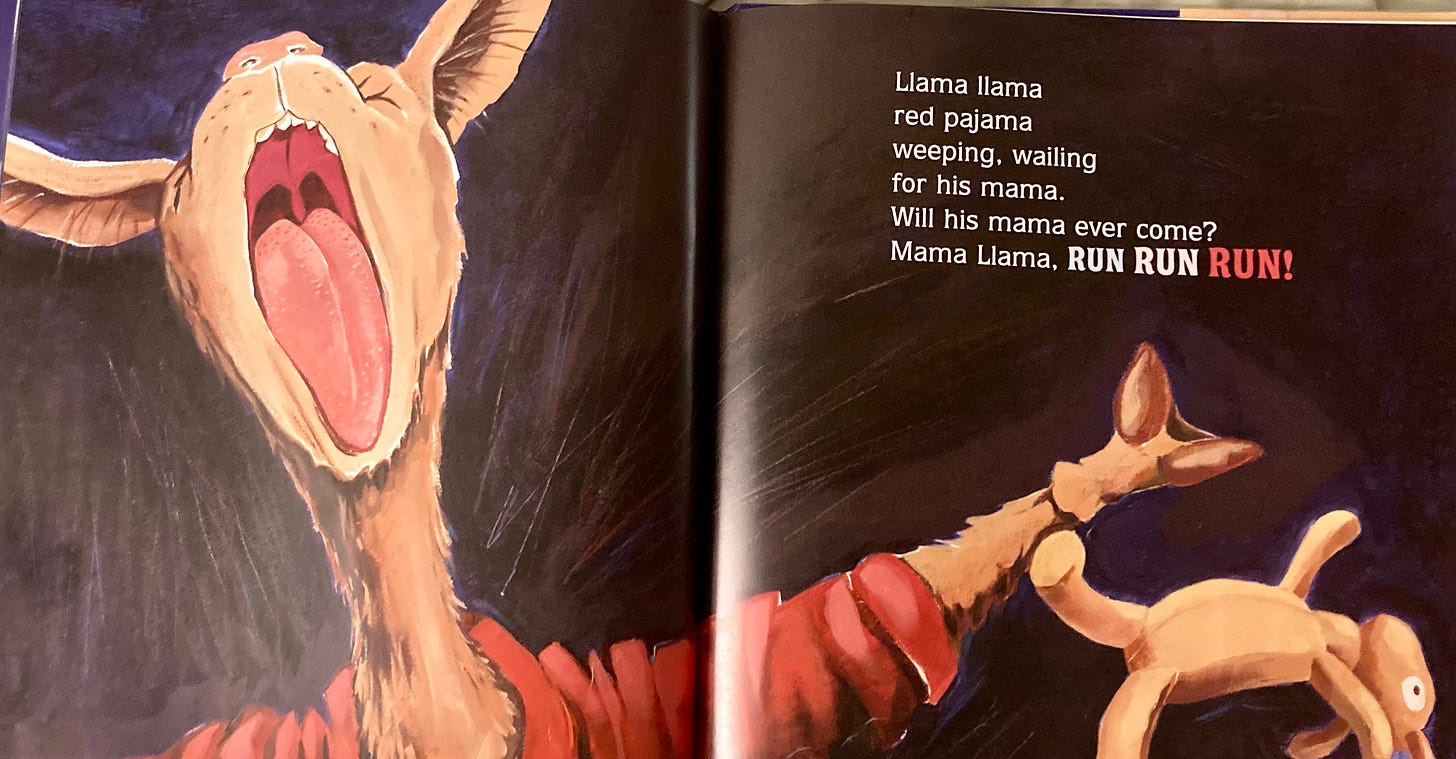

If you’ve read several of these books, then you might have picked up on the persistent theme of temper tantrums, melancholy, and melodrama sandwiched between big mama llama hugs. That seems to be the narrative arc of most Llama llama stories. There is also the conspicuous absence of Father Llama.

The objective of the series is doubtless to try to help children to understand and process their emotions. They show how trouble can arise and how children can deal with it. Most parents in the mainstream culture would laud this effort to help children cope with difficulties.

But I’m not in the mainstream. So let’s take a closer look.

These books actually become much more interesting, and you will be much more enlightened as to their purpose, if you read them from Llama’s perspective, rather than from his mother’s. The books begin to look like the heavy-handed attempts of an adult to normalize things that shouldn’t be normalized. For example, in Llama llama Holiday Drama, Llama is forced to endure an extended “holiday shopping season” (formerly known as Advent) with his mother. The ordeal involves much shopping, some baking (to bring cookies to school), and a lot of “dreidels, songs, and bells.” The closest we get to Christmas is in “woodsy smells.”

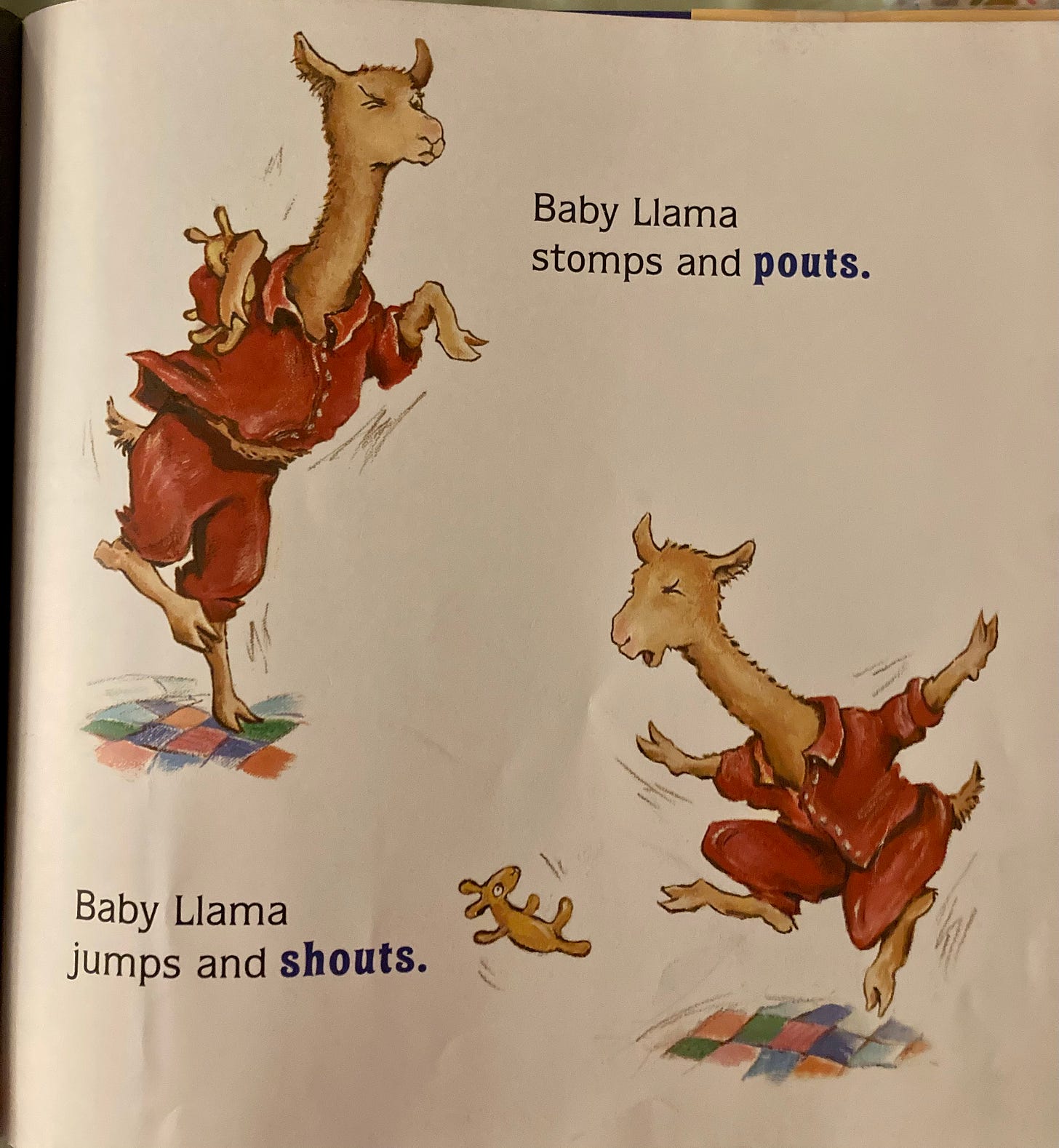

Llama llama has to buy a bunch of stuff and make a bunch of stuff and then wait and wait some more, and Llama gets tired of waiting. It all builds up to the climax:

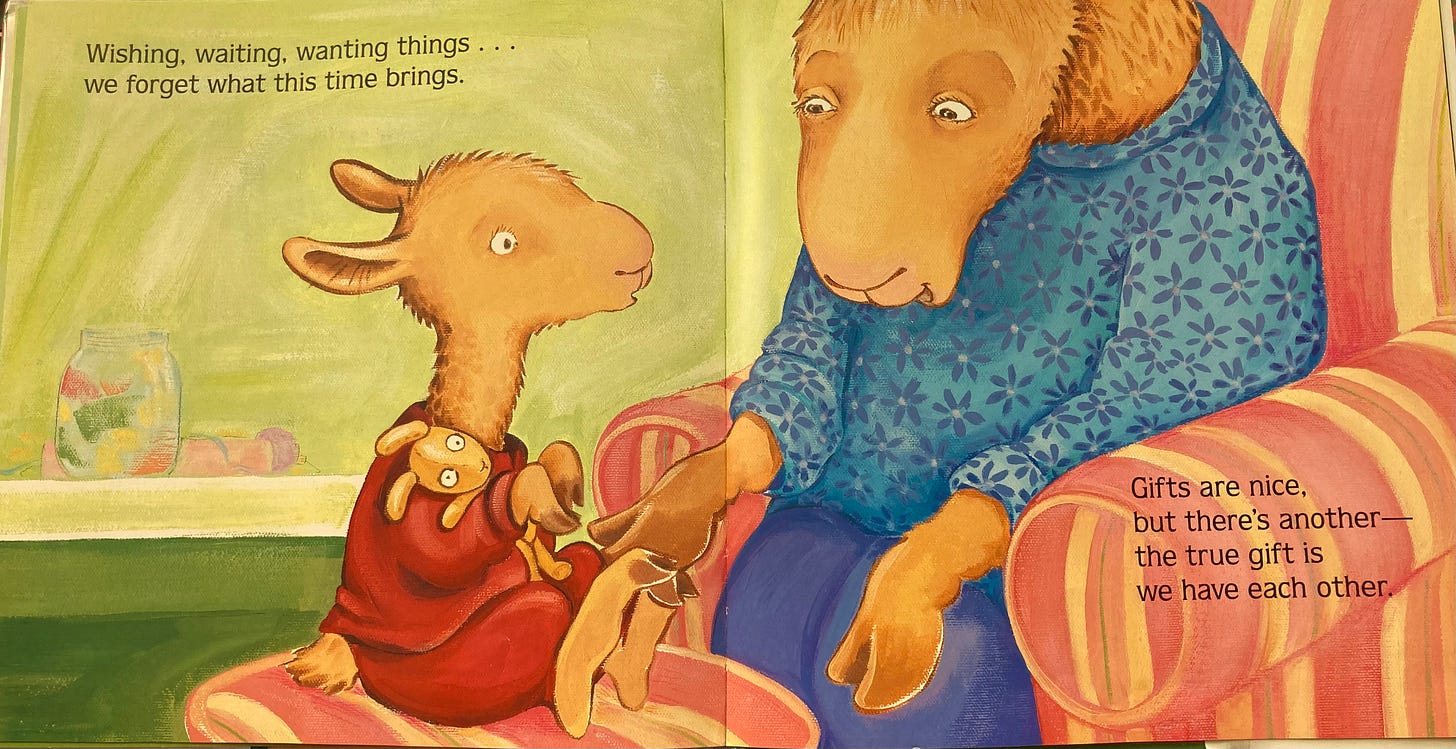

The “point” of this story is to show kids that it can be hard to wait for Christmas the Holidays™, but that it’s worth the wait because . . . well, there is no because. The conclusion is: “Gifts are nice, but there’s another— the true gift is we have each other.”

That this story has a clear “point” is the first indicator that it’s a bad children’s book, but that the “point” is just a sentimental undermining of Christmas (or even Hanukkah, if that’s what the Llamas celebrate) makes it even worse. “We have each other” is, and I hate to put it this bluntly, the divorced, agnostic mother’s way of coping with her own loneliness during “the holiday season.” It’s actually perfectly understandable why little Llama feels overwhelmed and confused about how many days are left before . . . before what? We aren’t told, and maybe he isn’t either. The poor Llama seems to be facing existential despair at the thought that something serious is impending, but he isn’t told much other than he has “12 more shopping days” left.

If this is what the Holidays™ are like, then we can hardly blame little Llama for his reaction. The shopping rampage and cornucopia of “stuff” disturbs his soul. And when poor Llama reacts to the consumerism and the nihilism as any sane person would, his mother gaslights him, telling him that he has simply forgotten what “it’s all about,” which is “having each other.”

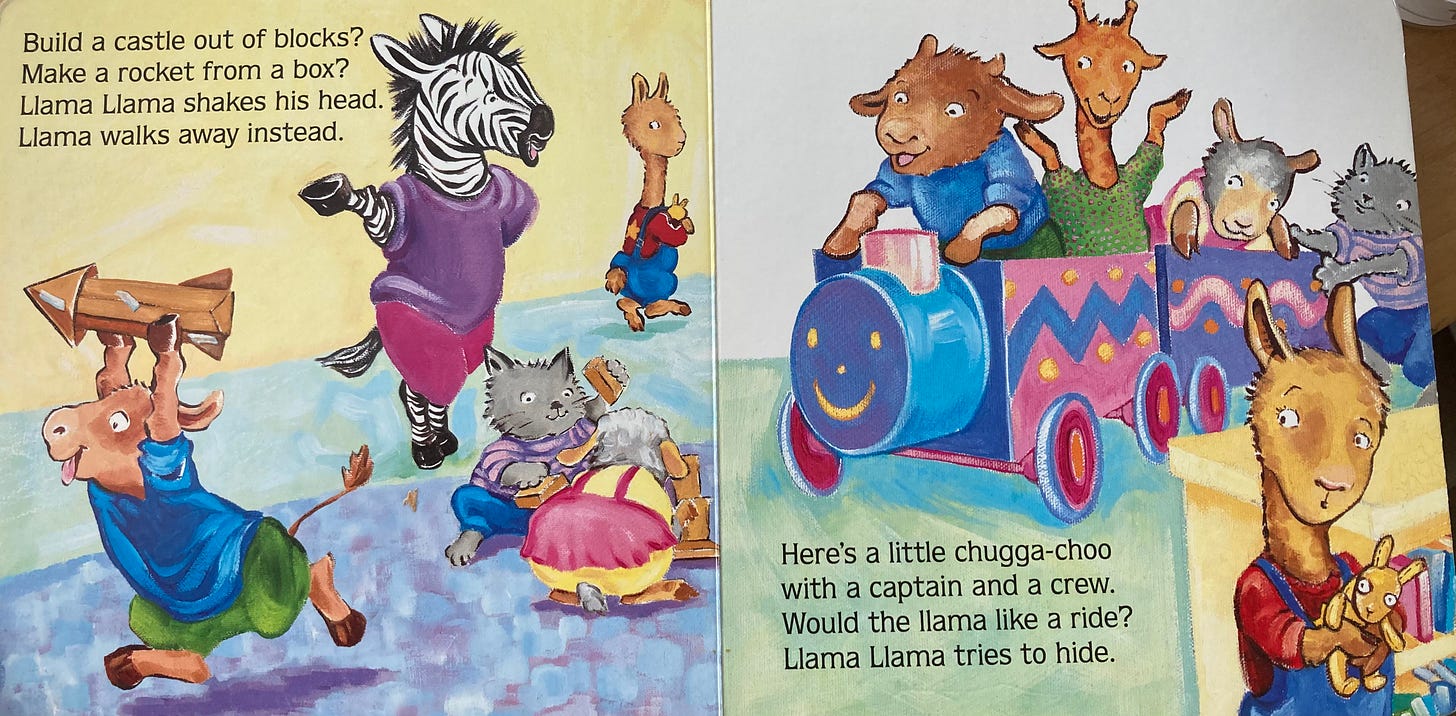

Is it, though? In Llama llama misses mama, poor Llama is told yet a different story. It turns out that just when Llama thought he had it figured out—that having Mama was the summum bonum—she tells him that he is about to be dropped off at daycare while she goes to work.

“Mama Llama goes away.

Llama Llama has to stay.”

Overwhelmed at his new second home, a veritable island of the Lord of the Flies, Llama feels shy, tries to hide, and then finally,

“It’s too much

for little Llama . . .

Llama Llama MISSES MAMA!”

He begins sobbing at the snack table, big tears falling onto his cracker and carrots. The other kids sit aghast at Llama’s display of emotion. The unlikely conclusion of this story is the happy adjustment of Llama to his new prison. Again, this is a story for mothers dropping their children off at daycare more than it is for the little ones being dropped off. Mom can rest assured that her child has long forgotten her presence by the end of the day and that he simply loves school. And yet, there are signs that perhaps this isn’t the case:

As if it can’t get any worse, Llama llama has to be away from mom yet again in Llama Llama Gram and Grandpa. This story is about Llama’s overnight visit at his grandparents house, and it cuts between scenes of Llama happily playing with Grama and Grandpa and then sadly remembering his beloved stuffy that he forgot.

Again, the author dwells on the difficulties of childhood, trying didactically to “show” children how to overcome their feelings. This author, and many parents, too, probably mistakenly believe that a young child reading about Llama llama’s overnight visit with grandparents sans stuffy will have some impact on the child should he forget his stuffy. But this is not how the imagination works, least of all the imagination of a young child. If children were allowed to read more about the good, true, and beautiful, and less about sadness, melancholy, and dysfunction, then they might be more adaptable to life’s vicissitudes.

The emotional swings between fun with grandparents and the melancholic longing for the stuffy only creates in the young reader of the story that same bipolar experience. We enjoy books, because we can relate to the narrator. Do we want our children dwelling constantly on feelings of anxiety, melancholy, sadness, and conflict, as these books do? Is this what we want to fill their imaginations with?

There is something sinister going on with these books. A story is as much about what is said as what isn’t said. And what isn’t mentioned in any of these stories about little Llama is a father. We know that this world is a broken place, fallen by sin. Death, divorce, and dysfunction are a sad part of many children’s lives. The question is, should the broken home be normalized? Even though we are never explicitly told, it is clear that Llama llama lives with his single mother. And it turns out that the author is a divorcée, so her desire to normalize her own situation is understandable.

I’ve mentioned a connection between the mental health crisis in young people and the romantic imagination. I think that these books give us a window into the way that the secular world tries to form children and how that “formation” contributes to their anxiety-ridden experiences. Rather than allow normalcy to be the norm in stories for children, these books try to normalize brokenness. Even children in situations of divorce deserve to have examples of wholeness, of God’s intention for family life.

What’s more, these stories center around emotional distress. I understand that the intent is probably to help children cope with these inevitable experiences but is the effect a beneficial one? Does it create peace and calm in the soul to read about experiences that, let’s be honest, children should not be having on a regular or even semi-regular basis. I have to wonder if the “lived experience” of Llama llama is not one peculiar to a child of divorce, in which case, his anxieties shouldn’t be presented as the normal experience of childhood.

I am not saying that one Llama llama book is going to corrupt the imagination of your child. Even a couple of them won’t do harm. But these books taken together and also in the context of the modern child’s home or school library, which contains more of the same, cultivates a certain quality of imagination—one that can be sharply contrasted with, say, the type of imagination that is fostered in Elsa Beskow’s Children of the Forest or C. W. Anderson’s Billy and Blaze.

One has to wonder if these books are meant for children or adults. Adults read them and get to feel like they are reading their kids an engaging story that also has a “good message” about “dealing with emotions” or dropping your kid off at daycare, or whatever. In reality, these books subvert the nuclear family, the stay-at-home mother, order and peace in the home, and traditional religion (Christmas). At the same time, they contribute to and normalize the feminization of culture. When the child is sad, confused, angry, overwhelmed, afraid—the response is always the same, “Mama loves you.” That is great, and mom’s love is undeniably necessary for children. However, children and especially boys need their fathers to show them a different kind of love and training and order. This complementarity is missing from the series, and is one of the reasons why your child shouldn’t be reading these books. Because, why read them? There are many, many children’s books out there. There is not a good reason to read these.

This is one of those pieces where every sentence is its own mic drop. Absolutely spot-on!

My baby is almost 3 months old so I've been looking at a lot of baby books lately. I've also noticed this creepy trend where older books are written for kids and newer ones are written for parents.