A friend said that someone asked her which books she should buy to teach her child to share. My friend, who shares my view of the imagination and the value of “living books,” knew that any book that tries to teach specifically “about sharing” is going to fail. It will inevitably be didactic and uninteresting to the child. What sounds more fun to you, reading a book out of the self-help section of Barnes and Noble or reading Pride and Prejudice? That’s how our kids must feel when given the choice between a “book about anger” and, say, Farmer Boy. They learn in the opening chapter about the ugliness and senselessness of violence and anger. It speaks to their imagination in an interesting and concrete way, unlike a kinder self-help book.

Today I’m going to review C. W. Anderson’s Billy and Blaze series. These books are wholesome, enjoyable, non-didactic tales about a boy and his horse and their adventures together. With three boys, these books have become something of a staple, and I’ve found myself trying to put my finger on exactly why they are so attractive, and what sets them apart from so much modern children’s literature.

First, there is a horse—er, pony. And this affords Billy the opportunity for adventure and exploration of which every boy dreams (and, as a girl, I too dreamed of this, so I imagine that these books are just about equally suited to girls, depending on their taste).

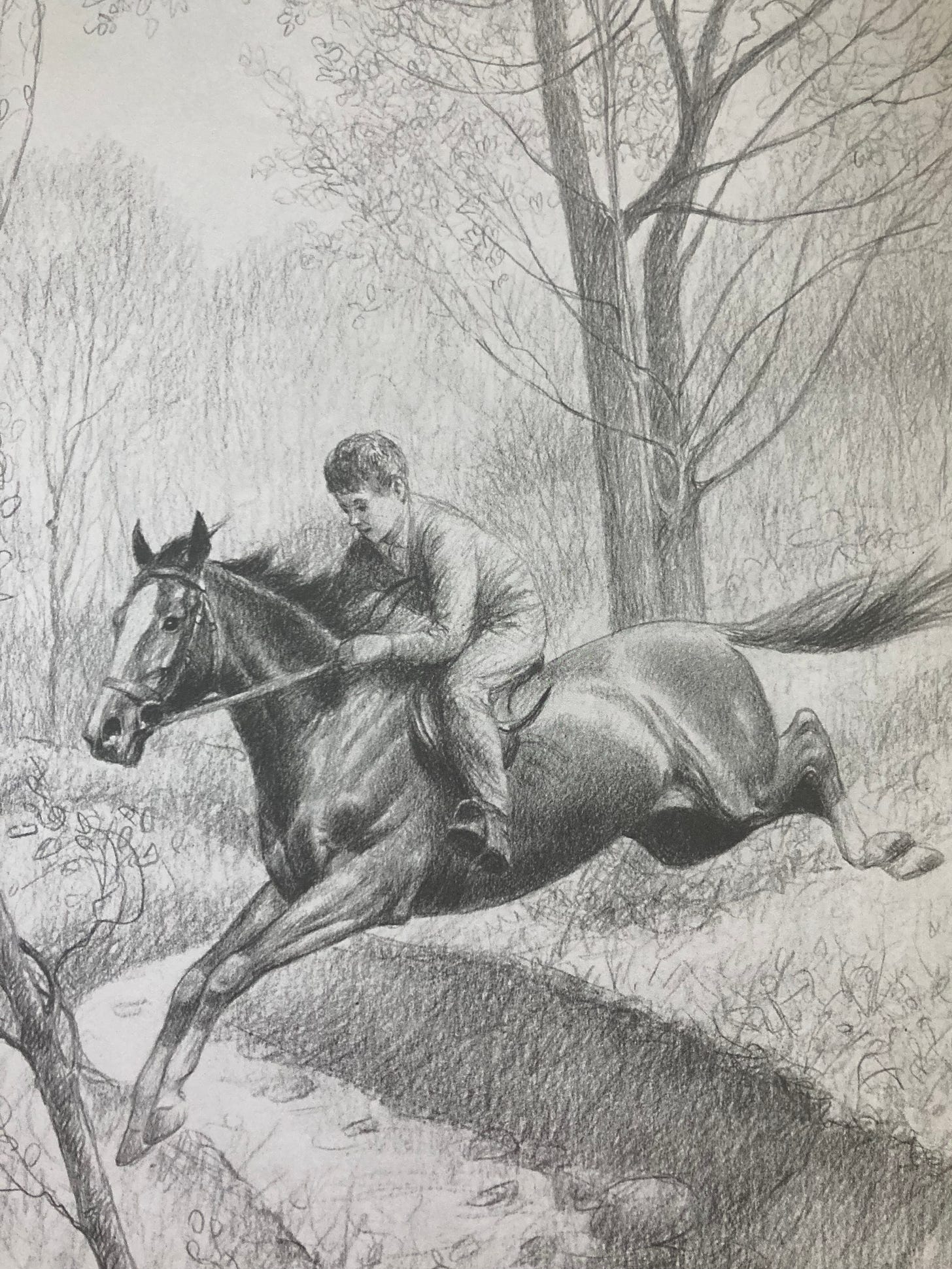

With the independence that his pony provides him, Billy is able to wander the countryside, travel down old roads, explore different terrain, encounter wildlife, and even mentor a young friend and his pony. The pace of the books is leisurely, yet they nonetheless captivate.

Billy and Blaze books offer escapism of a sort but one that is not dangerously romantic. Billy encounters the “wild and strange” in nature, one of the hallmarks of a Romantic tale and part of what makes it so appealing. Yet these stories do not veer off into the morally dubious land of unreality and abstraction, as so many modern children’s stories do. Billy enjoys his freedom and adventure while being bounded by the limitations of actual life. His mother and father have created a framework of order for him. Within this framework, Billy is able to enjoy a great deal of freedom, which, Anderson shows us, is tied to restraint.

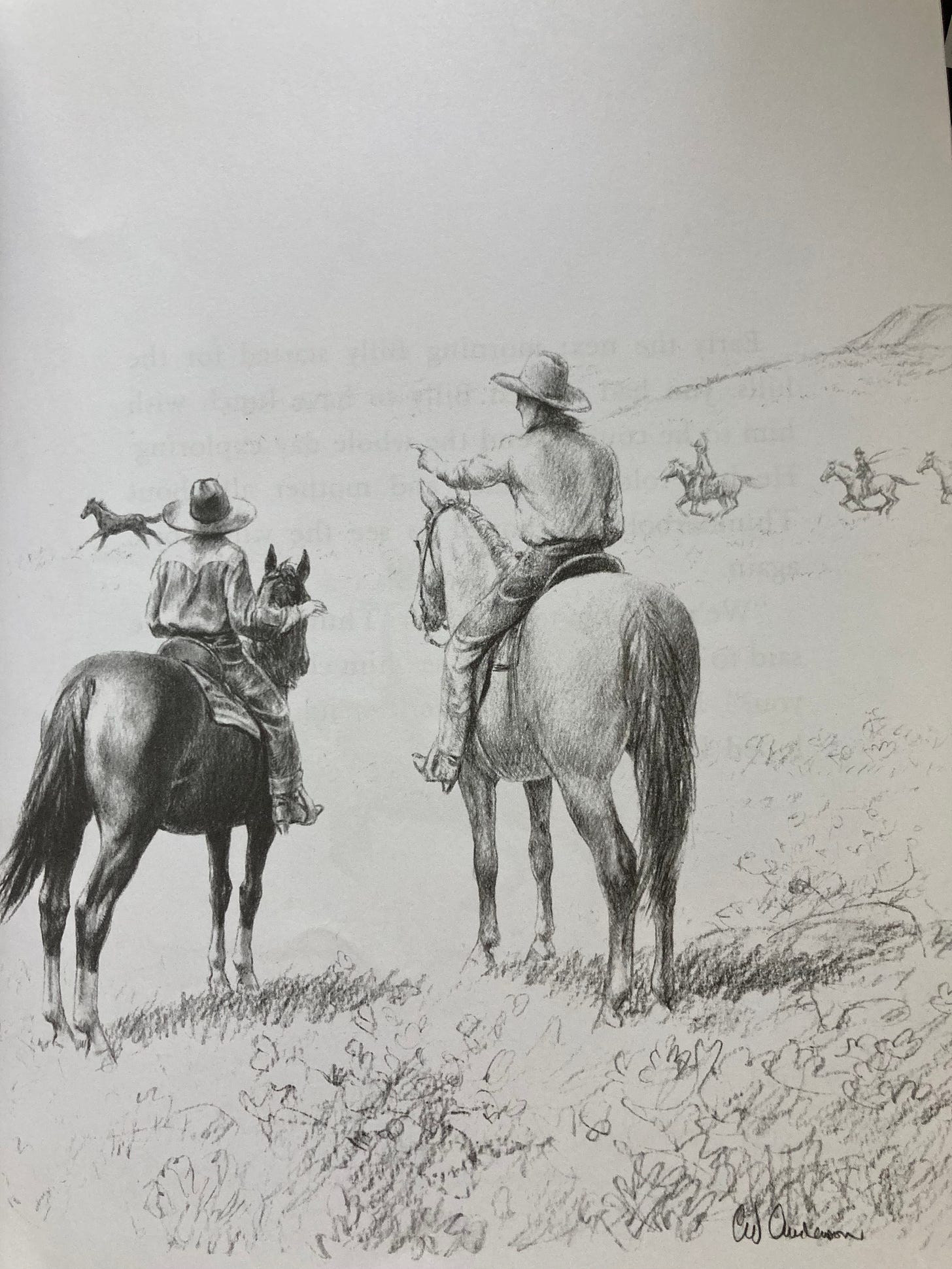

In Blaze and Thunderbolt, Billy travels out west for an extended vacation with his family. He encounters a friendly cowboy named Jim, who welcomes him to the area. Jim takes Billy out for a ride one day, and they see a wild black horse galloping across the desert plain pursued by a band of cowboys.

“‘That’s Thunderbolt!’ cried Jim. ‘He’s a wild horse everybody is trying to catch but he’s too fast for them. Look at him run! Isn’t he a beauty?’

Billy was glad to see that the cowboys were falling farther and farther behind. He did not want them to catch that beautiful horse. Jim told him that Thunderbolt was the last of the wild horses. Billy would have liked to follow him up into the hills but he was afraid his mother would worry if he was late for lunch.”

This short paragraph is packed with imagery that subtly nurtures the moral imagination. For one, Billy is allowed to explore. Yet he does not defy his mother. He knows that he must return for lunch. Nor does his mother nag him, for he has been given the freedom to roam far away. This subconsciously signals a great deal to the reader. It shows the respect that Billy has for his mother. It shows that Billy can be trusted with his freedom. And it does this because it does not aim to do this. There is a certain moral order that is a given. With that as background, a good story can be told.

Didactic children’s stories begin with the message, and then tell a story that is made to fit the message. Billy and Blaze begins with the adventure story, and the message does not need to be self-conscious because the moral framework is already a given. And children are able to sense that and the peace and order that it provides. They are able to enjoy the story for what it is.

A return to this kind of quality, non-didactic literature (Billy and Blaze was originally published in 1936) can help to reform the culture—and I mean that it will reform the minds of parents even as it forms the moral imaginations of their children. Good literature is good literature. It should be a pleasure for parents and children alike.

On the other hand, there are stories that are non-didactic and yet awful because they have forsaken the moral order. Love you Forever, which I recently wrote about, is one such story. Where Billy and Blaze show us the beauty and peace of ordered freedom, Love you Forever shows us the hideousness of anarchic freedom. The author tries to show us the humor of boys enjoying “freedom,” but really he shows us the chaos of a life without parental boundaries and spiritual formation. It does not present a realistic picture of what such a disordered life leads to—i.e. it does not lead to the normalcy that the story ends with: a father cooking dinner and rocking his baby after work (not that rocking your grown mother as if she were a child is normal).

In Blaze Finds Forgotten Roads, we are again given a taste of the type of ordered freedom that encourages the moral imagination, especially in boys. In this story, Billy heads out with his friend Tommy (who, we know from another story, is younger than Billy and looks up to him) to go exploring.

“Their mothers had packed lunches for them, and they were excited about their adventure.”

In that brief sentence, we again catch a glimpse of the fact that Billy’s expeditions are fully condoned by his mother (and father), who lovingly sends him off with nourishment for the adventure.

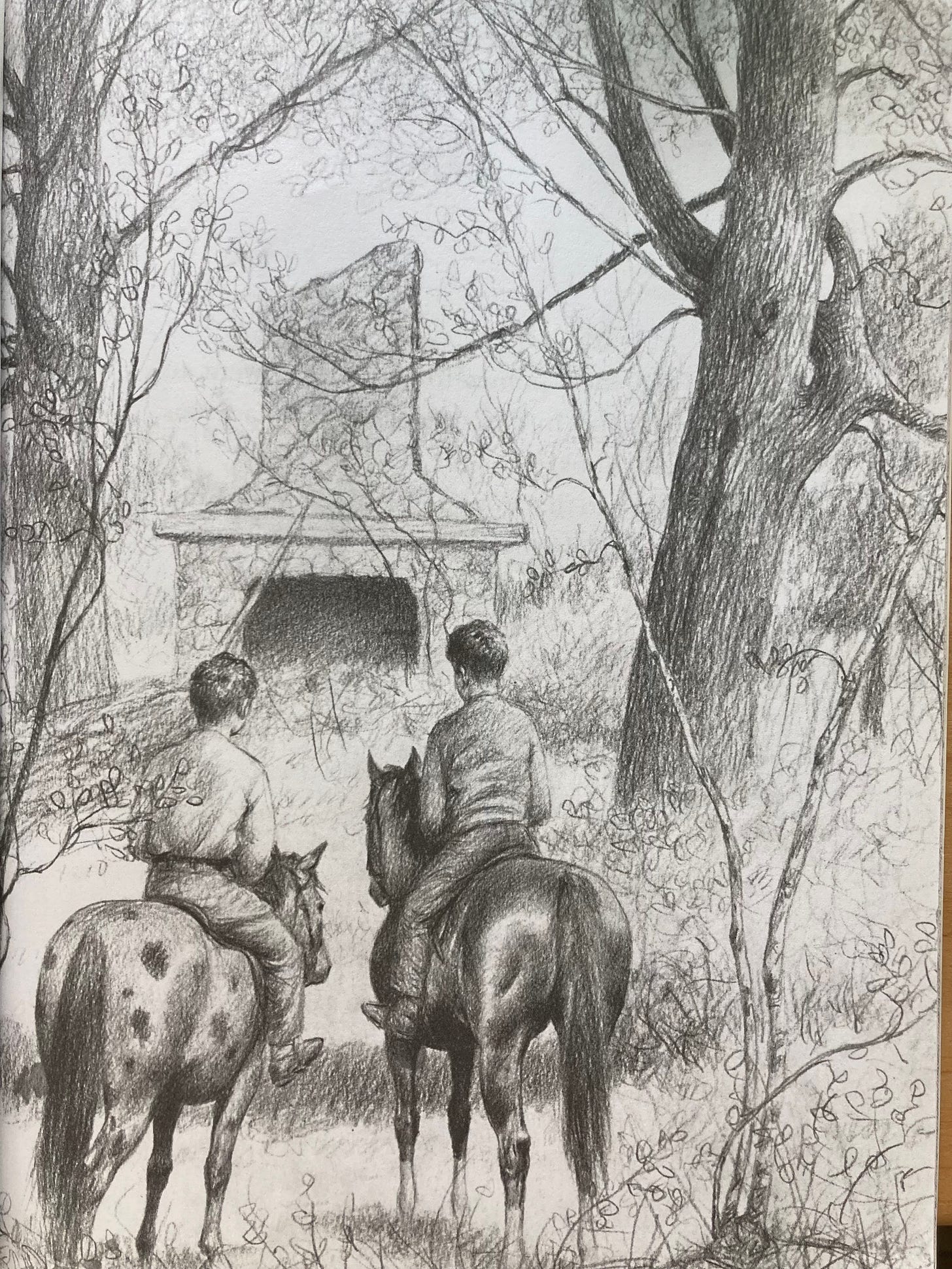

The boys push through bushes and over brush on their horses, straying into the forest to find something new and wonderful. Again, we have the allure of the romantic theme of untamed nature, yet tempered by Billy’s wholesomeness and deference to his parents. Billy, thank Heaven, is no romantic rebel. But at the same time, we are treated to the beauty of nature and the wonder of old, long-forgotten landscapes.

The boys happen upon a clearing and the ruins of a log cabin.

The two examine the ruins. Billy tells Tommy that the large, rusty hook inside of the fireplace was to hang a pot. “People used to do their cooking that way,” he says.

My own boys love to dig for old things and treasure. They fantasize about finding arrowheads and doubloons, and they love to stretch branches for bows and to whittle sticks to make arrows. Something about the idea of “the way things used to be” guides so much play and imagination in young kids (especially when it involves treasure and weapons!). This is the strange and mysterious element of the story that captivates the imagination.

Billy finds an old powder horn buried in the dirt. It happened to have the name “Billy Conroy” carved in. He thinks it special to be connected in this little way with a Billy who lived long ago.

Tommy finds an arrowhead on the ruins of the fireplace.

The boys continue on their journey, coming to a brook where they enjoy lunch, and later journeying through the woods as darkness falls. Anticipation and the feeling of a little danger round out the tale before their homecoming.

The other Billy and Blaze stories are equally enjoyable for young readers, especially boys, for their mixture of adventure, danger, and yet a certain realness that makes the stories feel possible. They are richly told, concrete, and at the same time wild and wonderful (yes, yes West Virginians). It is just what boys need.

I highly recommend the series for ages 4-10.

I couldn't agree more. Children's literature from that era particularly captures the best of human nature in all its aspects. The authors respected the reader (the child!). The artists gave their best. There is so much understanding of what it means to be a young boy in the Billy and Blaze books, and so much quiet happiness, peace, and order, within, as you say, a world of adventure and curiosity, but not too much drama.

I'm glad you wrote about these books! They are easy to forget about or overlook, but they contain a lot of wise pleasure.

This is such an important distinction in children's literature! I love the example that you have here, and I need to find my own copy for my boys. It seems (even though not having read this specific book) that adventure stories in this vein are calming and enjoyable to read.

Didacticism has always been (and, I suppose, will always) be a part of the children's literature conversation. We pass down ideas, morals, values, and more through story, so it does seem logical to "pick the moral" and then write the story. But, you discuss how this doesn't open up to good stories! I just posted about the French literary Beauty and the Beast and how that fairy tale, by it's second author - Jeanne Marie de Beaumont - was a didactic tale for young women. However, it was fit into an older, oral storyline, so perhaps that's why it's a story that endured!