Virginia Lee Burton against the Idol of Progress

The moral imagination is flexible, creative, and values continuity. (And a message for my paid subscribers!)

Right now, I have nothing behind a paywall. It is my hope that my writings can, in some small way, help to uplift the culture, and so I don’t want to restrict any of my work to just the few. However, I would like to reward the generosity of my paid subscribers who, thus far, have contributed out of a spirit of charity, so I am offering you the chance to submit a book title of your choice for me to review, and I’ll hold a lottery to pick a random winner. I’ll review anything, whether it’s Nietzsche’s Beyond Good and Evil (hopefully not) or Watty Piper’s The Little Engine that Could. It could be a novel, children’s book, poetry, a work of philosophy or religion—you name it! You’ll get the type of critical essay that I publish here at The Christian Imagination. I spend many hours on each of these posts and review each one carefully (as carefully as I can, anyway, in the midst of large-family chaos).

If you are not yet a paid subscriber, then become one, and you, too, can throw your literary hat in the ring!

Send your suggestion as a comment in this article or as a DM. I’ll put all of the titles into a hat and hold a drawing in two weeks, on April 24th (or thereabouts).

And on that note, a reader left a comment asking for a review of Virginia Lee Burton’s books, and I’m happy to oblige, for Burton’s stories beautifully illustrate the creative qualities of the moral imagination—and the ugliness that can lurk behind the idol of Progress. Many of her books illustrate that industrial-technological advancement is not an unqualified good, but at the same time, she is no retrograde. Burton shows that we can be skeptical, even critical, of so-called progress without simply lamenting it. We can accept the material reality in which we find ourselves while finding creative ways to mitigate some of its brutality.

The Little House might be her most well-known book. A winner of The Caldecott Medal (back when this meant something), this is the poignant tale of a “pretty Little House” that lives through the industrialized destruction of her countryside.

“This Little House shall never be sold for gold or silver,” declared the man who built her, “and she will live to see our great-great-grandchildren’s great-great-grandchildren living in her.”

Already we are caught off guard. Could such a wish (rather, declaration) ever come true in our modern age of rootlessness? An age in which we have been severed, seemingly irreparably, from knowledge of our (actual) ancestors and their ways? An age in which the houses have turned into McMansions even as family sizes have dwindled?

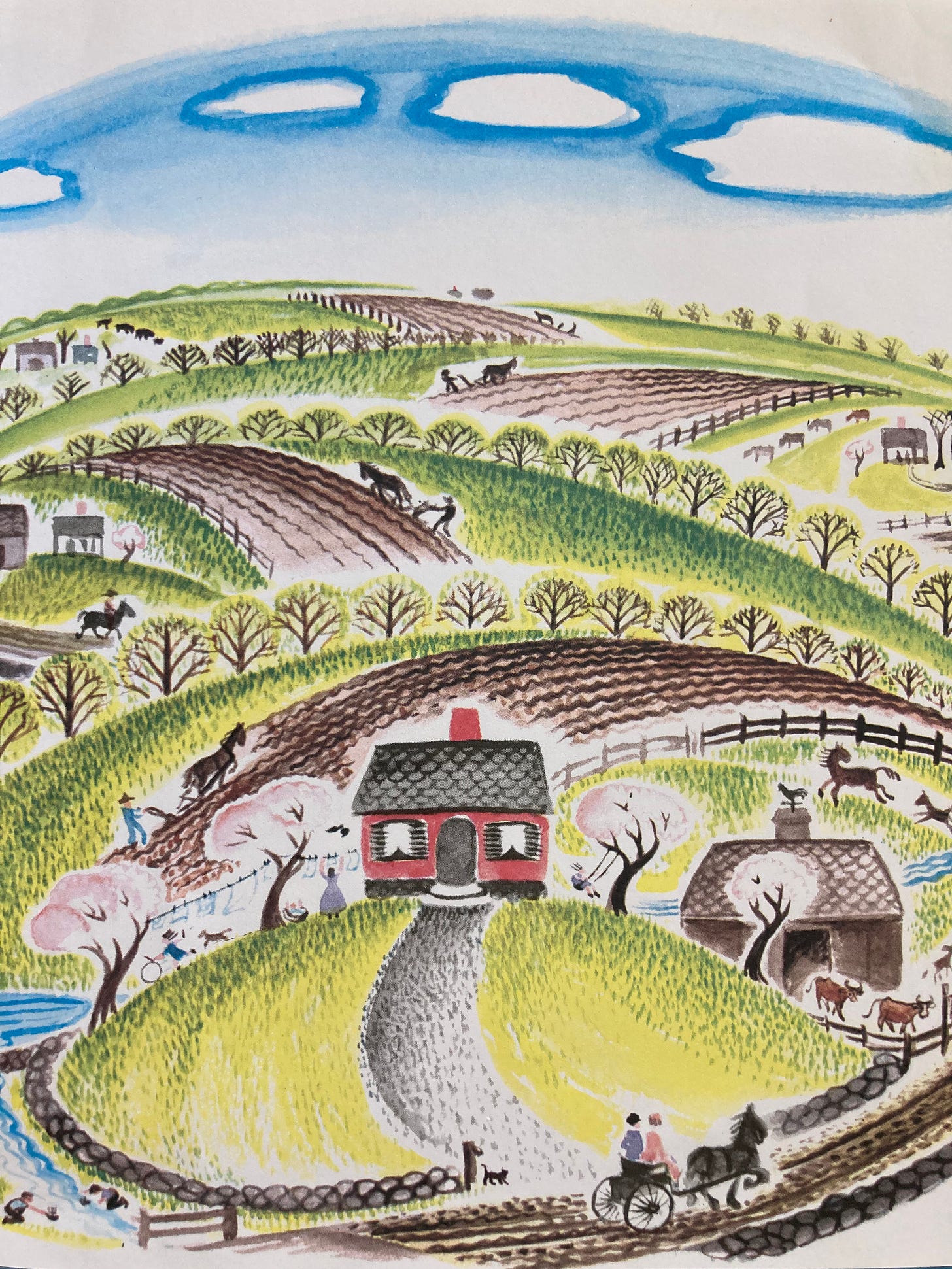

The book takes us through the experience of the Little House as Progress comes to her countryside. At its opening, the Little House is nearly alone amidst bucolic beauty, but soon she sees the lights of the city at night in the distance. She wonders what it would be like to live there.

Be careful what you wish for.

Slowly, the countryside around her changes, as dirt roads begin to stretch and houses dot the hills.

The seasons change. Children go to school. Winter arrives. We are given a glimpse of the divine view of time.

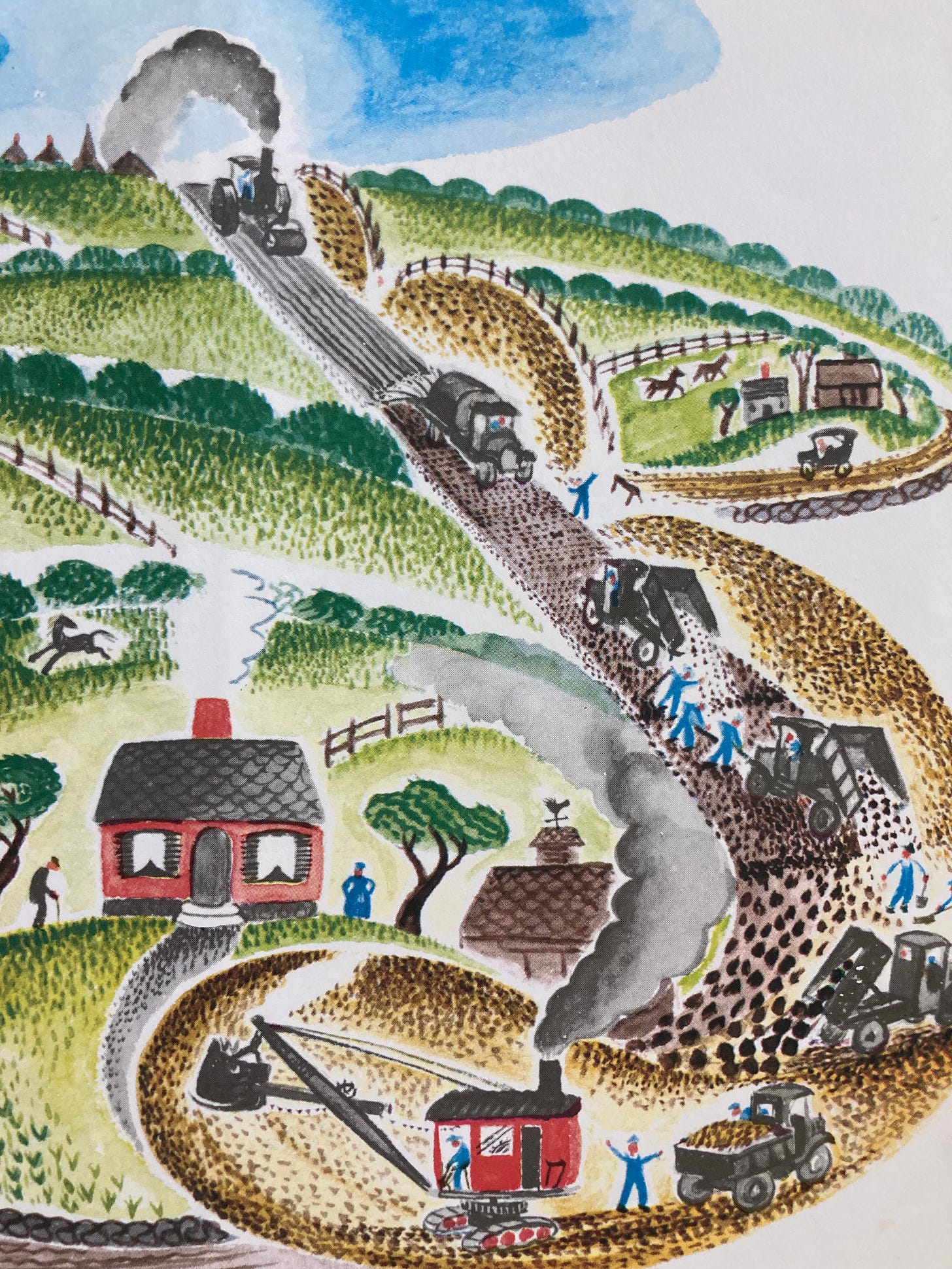

Then one day, “the Little House was surprised to see a horseless carriage coming down the winding country road. . . .”

Roads are paved and cars and trucks come and go.

I am reminded of Kenneth Grahame’s wariness of the “motor car” and his aesthetic exploration in The Wind and the Willows of the pristine beauty of the un-industrialized English countryside. The Little House, like Grahame, watches these horse-less carriages with curiosity as the landscape transforms with them.

“Everyone and everything moved much faster now than before.” In the age of such horror-conveniences as Amazon 2-day delivery, we can forget that people and mail and news traveled only as fast as horse-hooves and boats could take them. For children, the visuals that depict the transformation brings alive these major changes.

By gradually diminishing the verdant hills and darkening the color palette, Burton signals that the steamroller of Progress paves over the beauty and color of the natural world.

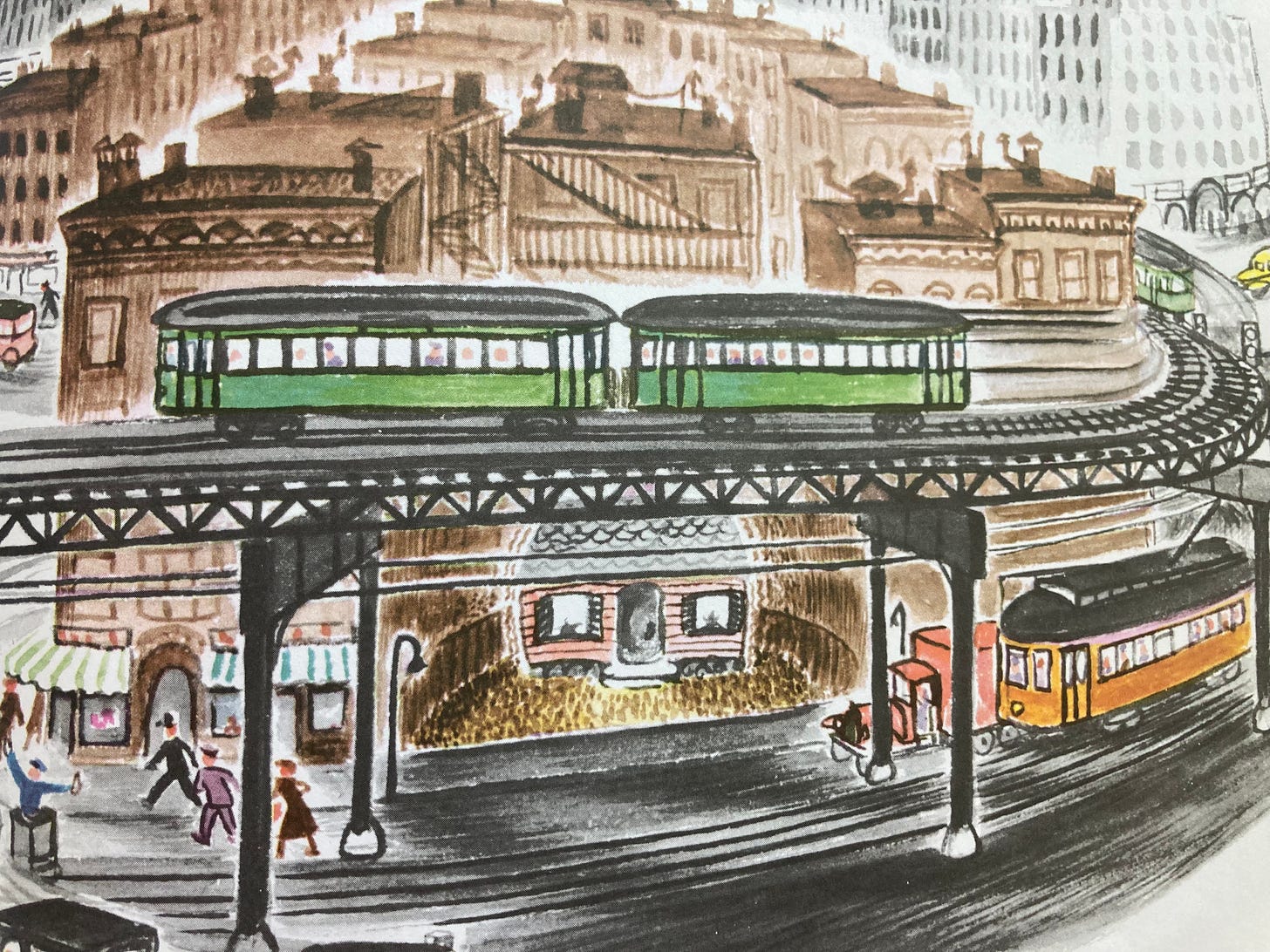

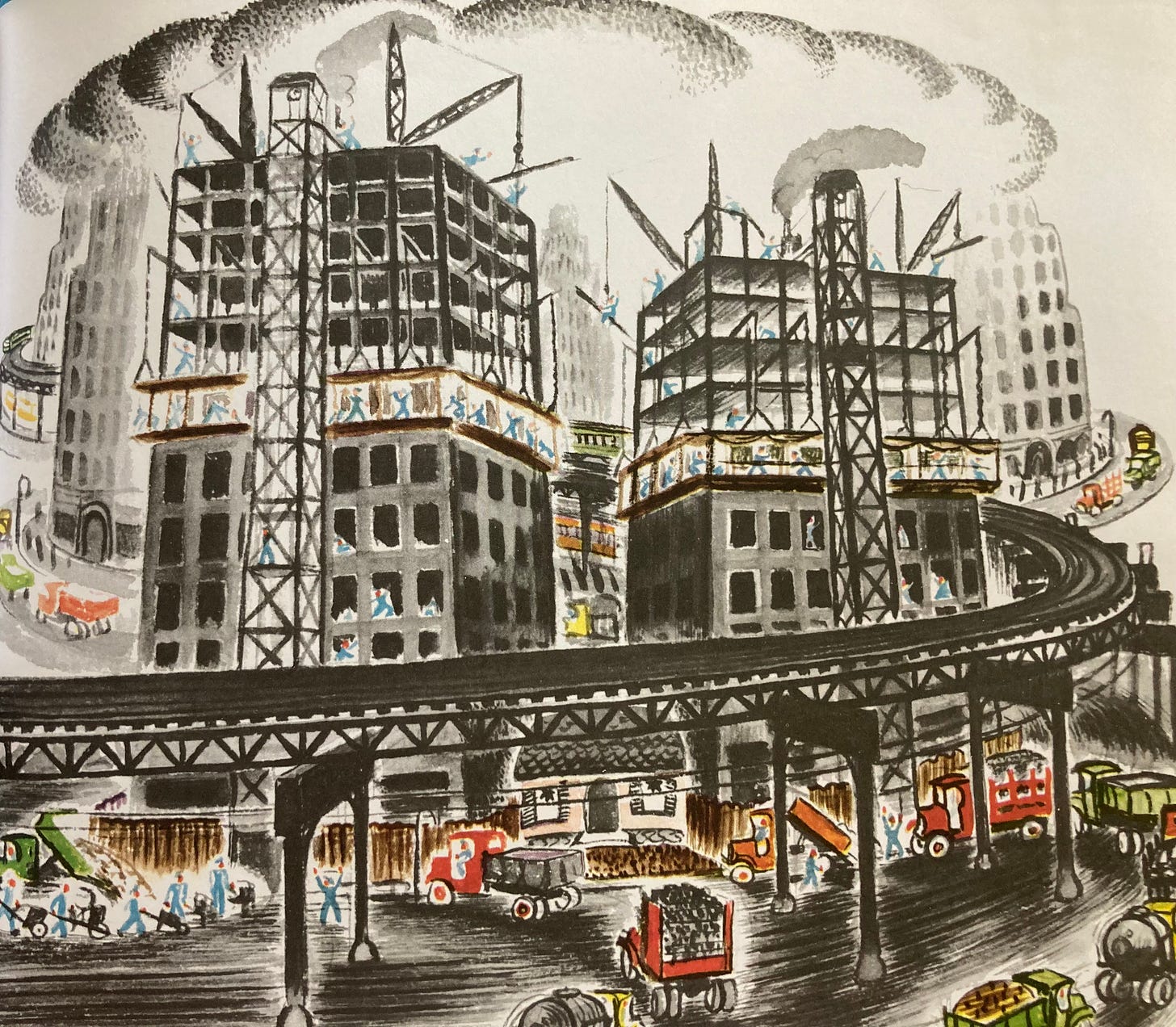

You think things are bad when the Section 8 housing goes up around the poor Little House—or is it just an industrial cityscape? But then things get even worse. There are trolley cars at first and then a train goes up right over the weathered old Little House. And still dystopia grows. The skyline creeps ever higher, towering over the once-pink little abode of pastoral serenity.

The colors grow bleaker as we confront the reality of modern, industrial Progress:

Smog hangs over the Soviet-style city (or, again, is this just New York City?). The population swells. You can feel the hustle and bustle and hear the incessant honking of cars.

And then, one day, someone stops in front of the boarded up old house and pauses. It was “the great-great-granddaughter of the man who built the Little House so well.”

“She saw the shabby Little House, but she didn’t hurry by. There was something about the Little House that made her stop and look again.”

She discovers that it is, in fact, her ancestral home and, God bless her, she has that well-built little old house picked up and moved out of that monolithic hellscape.

As the house begins to hear the birds and to see the green grass, she “doesn’t feel sad anymore.” She is fixed up, and settled down on a new foundation. “Once again she could watch Spring and Summer and Fall and Winter come and go.” Her curiosity about the city has vanished, and she can live peacefully in the country again.

I should add that, it is because of Progress that the poor Little House had to endure this trial, but it is also thanks to technology that she found a way out. I actually witnessed an ancient house that looked as if a strong gust of wind might blow it over, moved from one end to the other of a new development. Someone had the good sense to preserve this piece of history.

As readers, we are able to juxtapose the two different realities that Burton presents: that of the city and that of the country. Burton gives us a beautiful, and often untold, perspective of the countryside over which Progress has run roughshod. Kenneth Grahame had written of “two Englands existing together, the one fringing the great iron highways wherever they might go . . . The other, unguessed at by many, in whatever places were still vacant of shriek and rattle, drowsed on as of old.” This latter, “the England of heath and common and windy sheep down, of by-lanes and village-greens,” is the one that Grahame cherished and the one that is the setting of the Wind and the Willows.

There seems to be renewed interest not only in country living but also in the things of our past of which we have been deprived. At this juncture in the History of Progress, the great-great-granddaughter’s decision to remove the Little House to the country and to take up residence in it seems not only entirely rational but also the right and just thing to do. She honors her great-great-grandfather’s desire that his house be lived in by his progeny. And she herself makes her own escape from a cramped and hurried existence apart from God’s creation and the natural order of existence. The reunion of the home and its rightful owner is actually threefold as the two are reunited with the natural world. There is a sense of supreme serenity at the end of the tale, that all is right in the universe. At the end, when the little house is rescued, my children seemed to heave a huge sigh of relief. Thanks to Burton, hopefully mine will never “wonder what it would be like to live in a city”!

Mike Mulligan and His Steam Shovel is another delightful story about a man and his steam shovel, “Mary Anne,” and how they must adapt to the dislocating changes of industrialization. Mike and Mary Anne had helped to industrialize America, digging the great canals for ships, cutting through mountains for trains, flattening hills for cars and trucks, making landing strips for airplanes, and digging out the cellars for the construction of skyscrapers. Children can get a little history lesson about how the Panama Canal was dug and how the railroads in America were laid.

Mary Anne was a handmaiden of Industrial Progress. Until one day, Mike Mulligan discovers that Progress has overtaken them, and suddenly the “age of steam” is at an end. “[A]long came the new gasoline shovels and the new electric shovels and the new Diesel motor shovels.” The services of Mike Mulligan and Mary Anne are no longer needed. (One is reminded of the poor gas-powered lawnmowers in California, soon to be outlawed for sale—except, of course, on the blackmarket, where they will go for a fortune.)

Like the Little House, the protagonist of this book finds solace by going to the country, to the little town of Popperville, where folks had just gathered to decide who should dig the cellar for a new town hall. The big advanced cities might be too cool for steam power, but the small towns are slower to adopt change—and this isn’t a bad thing, Burton seems to say.

One is given not only a taste for humane life in the country in this book but also for the spirit of American enterprise. Mike Mulligan and Mary Anne promise to dig the cellar in just one day. “If we can’t do it, you won’t have to pay.” They represent the hard-work and resiliency of the older America that we used to know—the one where humble folks in the country could simply run a small business without having to cross an ocean of regulations with a millstone of permits strapped around their necks.

As the duo begins their work, a little boy comes along to see.

“Do you think you will finish by sundown?”

“‘Sure,’ said Mike, ‘if you stay and watch us.’ We always work faster and better when someone is watching us.’”—again, the opposite of the American I have grown to know in which the contractors who bid for city jobs seem to work best when no one is watching them. But it’s nice to remember that things used to be different, and that they could be different.

The town folk come to see Mike and Mary Anne digging. They gather and wait with anticipation. The sun rises higher in the sky. Mike and Mary Anne dig faster, and still faster. A wild cloud of smoke and dust rise and nearly obscure them.

“Then suddenly it was quiet.

Slowly the dirt settled down.

The smoke and steam cleared away,

and there was the cellar

all finished.”

Everyone cheers. Then, the boy realizes that Mike and Mary Anne are, in fact, stuck in the cellar hole. They dug so fast, they hadn’t considered a plan for their exit. If only, Gavin Newsom sighs, Mike and Mary Anne had done the proper permits and paperwork this could have been prevented.

Everybody in town starts to bicker about how to solve the problem. Then, the little boy chimes in and says that Mary Anne can just stay in the cellar and “be the furnace for the new town hall and let Mike Mulligan be the janitor.” Burton’s clever solution gives children a metaphor for adapting to life’s unexpected turns. The world had to adjust to the arrival of steam shovels, and now the steam shovel must adapt to the arrival of new technology.

However, this isn’t a tale of simply accepting Progress as unavoidable. Burton shows that we can to some extent mitigate its affects on our lives by removing ourselves to the country or to small towns. This might have seemed like a pastoral dream— the type of unrealistic romantic longing against which I have cautioned—prior to the age of Covid, but now, with new possibilities for remote work, this is possible for some people. Others are simply finding ways to make life in a rural economy work, given the positive benefits that life affords away from major cities and the stomping grounds of the bicoastal elites. And still others find ways, even amidst life in a bigger city, to cultivate little religious enclaves, shelters from the mainstream anti-culture—places where technology is slower to be adopted.

Burton’s book Maybelle the Cable Car explores similar themes of progress through a look at the citizens of San Francisco’s efforts to save cable cars, an outdated form of transportation but, so the city decides, a desirable one. We don’t always have to accept Progress as a fait accompli. We can—or we used to be able to—fight this at the local level.

Burton encourages us to find creative ways to work around certain givens, and at other times to fight the destruction of Progress. It takes an imagination that is able to roll with the punches. The moral imagination, far from being some buttoned-down puritanical thing, is a living force able to contend with the opposing forces of evil. It recognizes that sometimes, things are so far gone, we must pack up and leave for the country. At other times, it sees potential in concrete political action. And still other times, it sees how we can work with current conditions to make the most of things. In all of these instances, at the background, Burton shows the importance of tradition and continuity, and the lurking danger of severing ourselves from our past in the name of “progress.”

Burton illustrates these ideas concretely, showing children the beauty and flexibility of the moral imagination.

I would love an article on commentary on Studio Ghibli films if possible - “My neighbour Totoro” “Kiki’s delivery service” “Princess Mononoke”.