I often ponder what it is about Arnold Lobel’s stories—Frog and Toad, Owl at Home, Mouse Tales, and Grasshopper on the Road—that makes them so appealing. Lobel himself admitted that these stories were as much for adults as for children. But Lobel also said that he wrote children’s stories by imagining what children would want to read. The Frog and Toad characters, he says, were inspired by two different facets of his own personality—which is why I think these characters are relatable. Lobel started with the particular, but he does not end there. He illustrates universal aspects of human nature.

Art and Laraine Bennett’s book The Temperament that God Gave You outlines four temperaments—choleric, melancholic, sanguine, and phlegmatic—to help us better understand ourselves and those we love. Frog represents the sanguine and Toad the melancholic temperament. As the Bennetts say in their book, we all have elements of all of these temperaments but one is usually dominant. It is good and healthy for us to try to balance what we are naturally inclined toward with what we are not naturally inclined toward. Thus, the melancholic Toad ought to try to get out of bed and go exploring sometimes, even if he doesn’t feel like it.

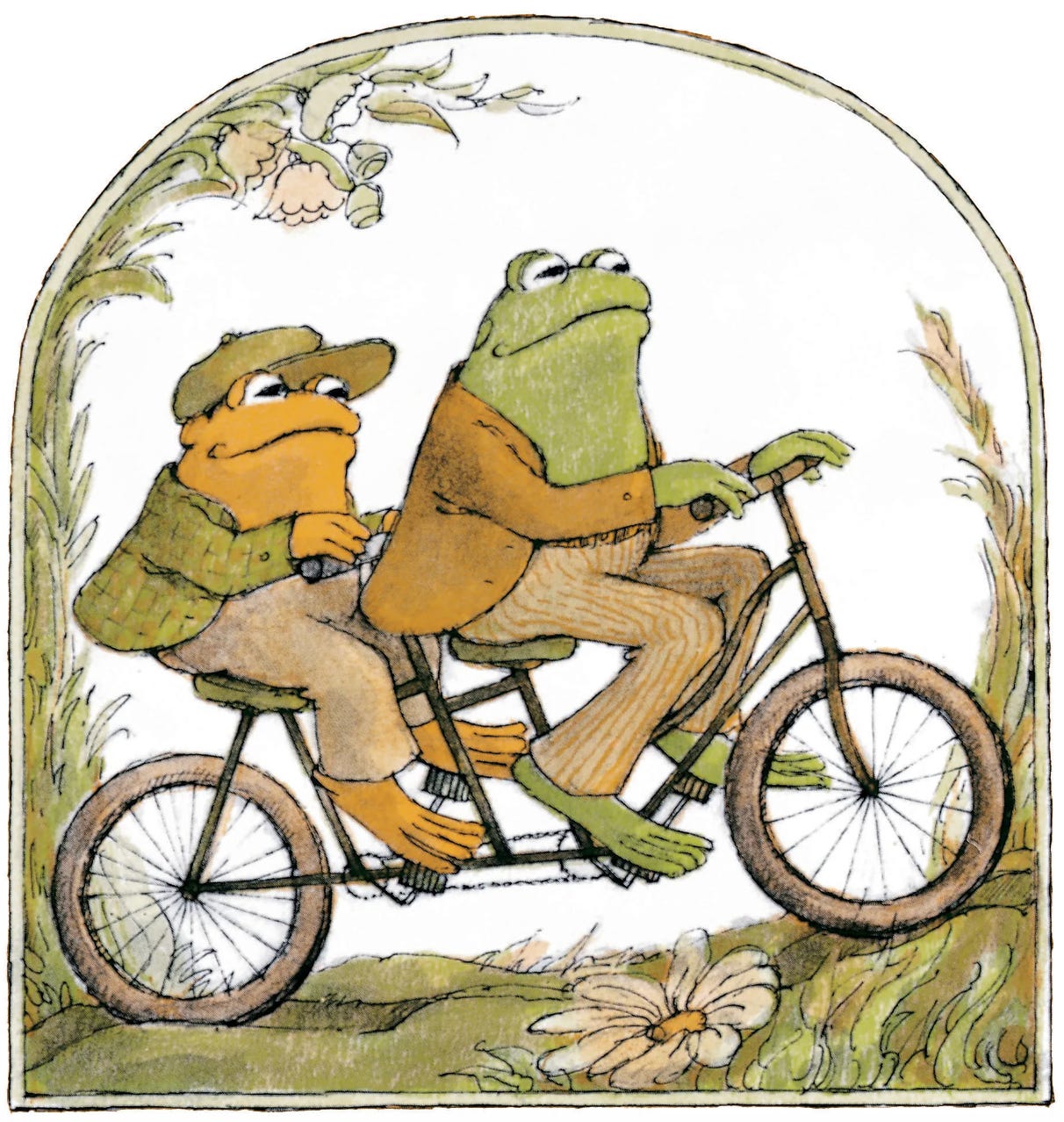

How often does Frog coax an unwilling Toad to get out and enjoy life? He convinces him to bundle up and go sledding rather than lie in bed; he convinces him to get up and enjoy spring (okay, he dupes him in this one, but he still gets him out!); he encourages him to keep trying to fly that kite, even against the jeers of the sparrows.

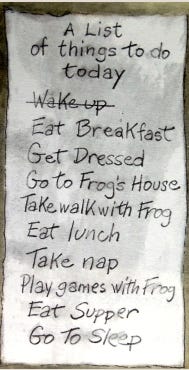

A funny example of the melancholic, neurotic Toad is “A List.” In this story, Toad decides to order his day by writing everything he plans to do on a list:

“There,” said Toad. “Now my day is all written down.”

He got out of bed and had something to eat.

Then Toad crossed out:

Eat BreakfastToad took his clothes out of the closet and put them on.

Then he crossed out: Get Dressed.

But later in the story the wind catches his list and Toad loses it. Frog, bless his heart, tries to track it down, but the list is gone. Toad is paralyzed. Without his list, he complains, he cannot do anything. At last, though, as the two tired creatures nearly fall asleep, Toad remembers something from the list: “Go to sleep!” “That was the last thing on my list!” He writes it in the sand and crosses it out. His OCD has been satisfied, Frog is pleased for him, and the two drift off to sleep.

This is a fun one for us because the boys like to write their own silly lists. We joke about not being able to do something because it’s not on the list. This little exercise, which arose spontaneously one time, is a fun bonding activity and gets us laughing together. But it also serves another purpose. This story illustrates the bureaucratic, task-master mindset to which we can all sometimes be prone (“The Voyage” from Lobel’s Grasshopper on the Road illustrates a similar idea).

The children are able to meditate, unconsciously, on some deeper ideas. These ideas don’t penetrate at a rational level but at an intuitive or aesthetic level. Perhaps one day they will be able to rationally articulate these ideas. But that is not the point at this juncture. It is not important to philosophize the story. The story itself conveys its truth and its moral good intuitively and subtly.

The tendency of the melancholic toward neuroses is also on full display in the story “Alone.” Toad goes to Frog’s house and discovers a note on the door that says, “Dear Toad, I am not at home. I went out. I want to be alone.”

Toad assumes the worst. He must have offended Frog. Frog no longer wants to be his friend. He has run away to escape him! Toad tracks Frog down finally, only to discover that Frog really did just want to sit and enjoy the beauty of his life alone, and there was nothing more to it!

The story “Christmas Eve” tells a similar tale of Toad battling his melancholic fears. Frog is late for their Christmas Eve celebration and Toad assumes the worst. Just as he has gathered up his strength (and his tools to battle the forces of darkness), Frog shows up. He had been wrapping Toad’s present he confesses.

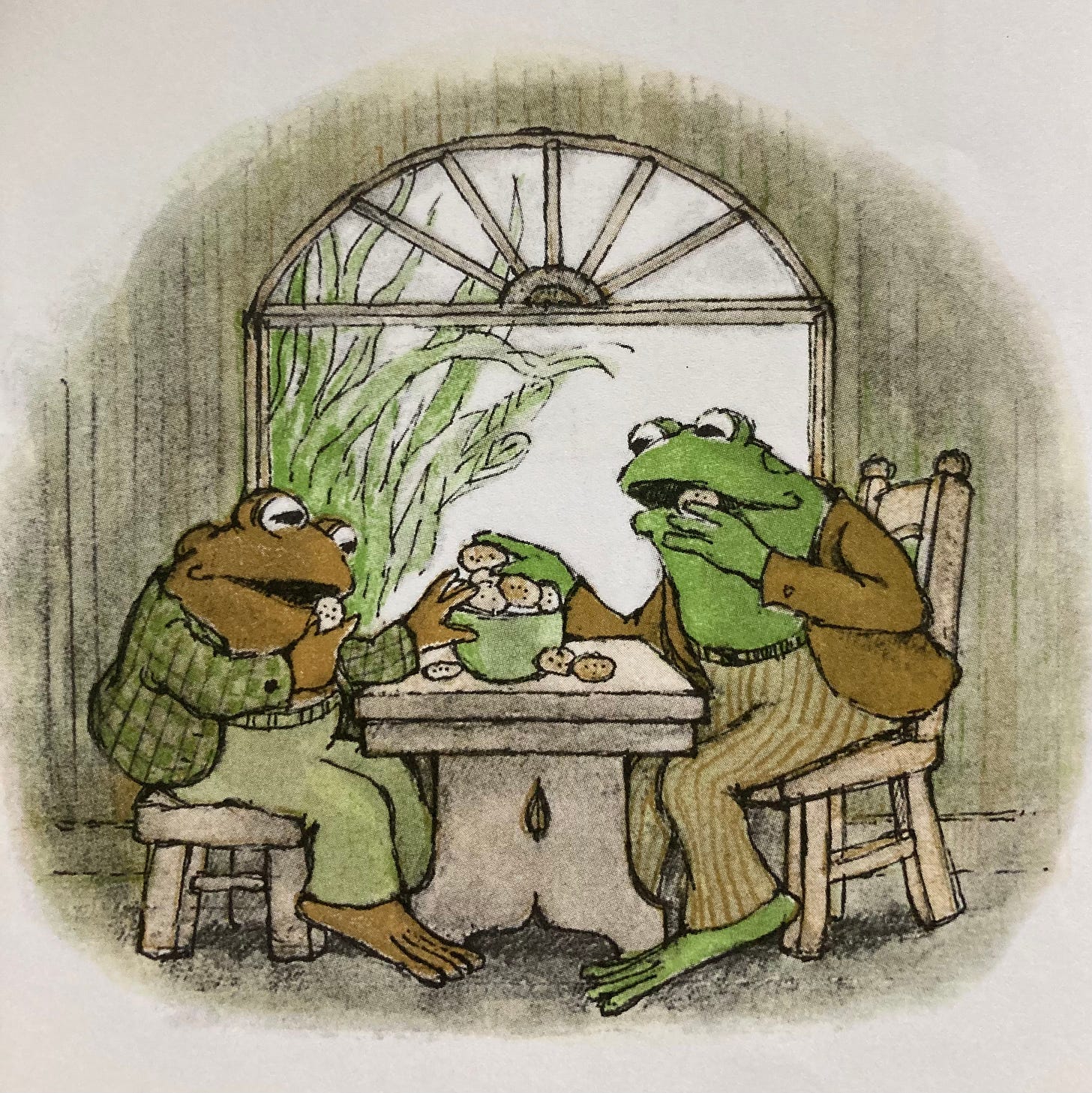

We get to see the mind of the sanguine Frog at work in one of my own personal favorites, “Cookies.” In this one, Toad has baked up an enormous batch of delicious cookies—“the best cookies I have ever eaten,” according to Frog. The two sit and gobble. And gobble some more. They cannot stop eating the cookies.

“You know, Toad,” said Frog,

with his mouth full,

“I think we should stop eating.

We will soon be sick.”

“You are right,” said Toad.

“Let us eat one last cookie,

and then we will stop.”

They at one last cookie. And then Toad said, “let us eat one very last cookie, and then we will stop.”

But they could not stop.

We can all relate.

Finally, Frog states the obvious: “we need will power.”

“‘What is will power?’ asked Toad. ‘Will power is trying hard not to do something that you really want to do,’ said Frog.”

The rest of the story is Frog trying to make the cookies increasingly difficult for them to access, first putting them in a box, then tying the box, then putting the box out of reach, until at last, they discover that they can always get the box if they want.

Frog and Toad are trying to make will power something external. The humor is that, in the end, they have no will power and so they throw the rest of the cookies to the birds. I won’t spoil the ending, though. I still remember my pleasure reading this story for the first time!

Part of the appeal of “Cookies” is that Lobel is commenting on the difficulty of having will power and that, in the end, it must come from within.

This is another story that, although short and seemingly simple, shines a light on the human condition. Its message has seeped into our household’s collective consciousness because we often (admittedly, too often) find ourselves saying, “one very last _____” as we reach for another cookie or brownie. Thus, even the children acknowledge their gluttony—even as they grab that very last cookie. Let me be good, Lord, but not yet, to paraphrase St. Augustine!

In the same volume as “Cookies” is the little gem “The Dream.”

In this story, Toad dreams that he is on stage in a theater. A mysterious voice announces what Toad will do “very well” as Frog sits alone in the audience. As Toad performs, Frog becomes smaller and smaller.

The message of Toad’s dream is that pride is the ruin of friendship. It is a warning against the temptation to try to outdo our friends, something that the young can be especially prone to. As Toad seems to grow in importance, Frog shrinks. In the end, Toad is fed up and shouts at the voice that has been proclaiming his greatness, “shut up!” Toad chooses friendship over his own glory.

Yes, Lobel did leave his wife to move in with his partner in Greenwich Village and later died of AIDS. However, Lobel’s personal failings seem not to have infected his literature. This is because, I would argue, Lobel does not try to insert his own personal, idiosyncratic views or imaginings into the literature. He taps into something universal through his understanding of human nature. He reflects on his own, at times, neurotic melancholy and, at other times, sanguine outgoingness. He is able to leave behind his personal life and politics and sticks with what he sets out to do, write books that children will enjoy (and adults too).

The concrete plots of these stories that are at the same time layered with wit, humor, and subtle commentary on the human condition make them enjoyable stories for all.

Stay tuned for Part II, in which I explore Lobel’s Owl at Home and the romantic mind of the child.

These are listened to and read on repeat in my house!

Thank you for this article! I must live under a rock, because I'm not sure that I ever heard of these Frog and Toad stories. It's making me think I'll have to request these at the local library sometime (and let the librarian laugh at the idea of an almost 20-year-old woman taking out a children's book).