In the first post in this series, I gave a sketch of some of the elements and figures of the Romantic movement, a movement that unleashed a whirlwind of creativity, imagination, incredible beauty in the visual arts, and a rejection of didacticism in the literary arts. Romanticism rightly criticized the empiricist, utilitarian, and overly rationalistic orientation of Enlightenment thinking, which had gone so far as to try to bring everything from morality to politics under the purview of instrumental reason. In the eighteenth century, Europe was fast becoming disenchanted, as Max Weber would later term it.

Rejecting the Enlightenment decoupaging of human life and reality, Romantic artists, literary figures, composers, and philosophers began to stress the non-rational and imaginative dimensions of existence. Spontaneity, feeling, and emotion came to be seen as proper human experiences, and ones that should not be suppressed. The desire for a “return to nature” was a part of this. The sterilizing effects of the Hobbesian idea of God as watchmaker combined with scientific naturalism (the laws of nature alone determine history and reality), led to a renewed desire to enjoy nature in its uncultivated state and to regain a sense of wonder.

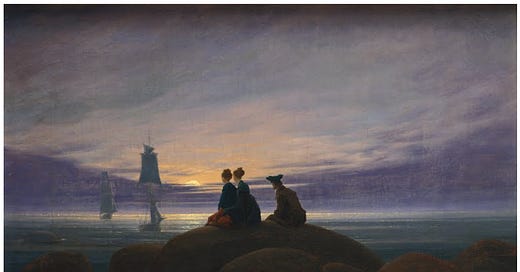

The visual arts often depicted the dark, melancholic (sometimes perverse) side of man’s psyche. The Gothic genre emerged from this movement. Landscapes (if they included human subjects) tended to depict nature as vast and awe-inspiring and man as but a small figure within it. Where the Enlightenment scientism of Francis Bacon would have man as the master of nature, Romantics posit nature as the real master.

To illustrate some of these characteristics of Romanticism, I examined the captivating and dramatic series of paintings The Voyage of Life by Thomas Cole. I have these prints hanging in my home, and I think that they represent some of the finest work of the Romantic imagination.

Although Cole was a Christian, when I look at this series, I see the distinct stamp of Romanticism over its Christian symbolism—or perhaps his Christianity interpreted through the lens of Romanticism. Indeed, in the paintings the man’s struggle and agony depicted in his manhood and old age represent a very Christian idea. However, the emphasis on man’s smallness as compared to nature; the spiritual nature of existence that eludes the vainglorious; the idyll/despair dichotomy; and the use of nature as allegory for the feelings of man all represent quintessential Romantic themes. The depiction of life bifurcated between the two extremes of exuberant hope and utter dejection, with little in between, is one of Romanticism’s hallmarks.

However, art is never one thing. Cole’s paintings are not “merely” Romantic. There is doubtless a Christian spiritual dimension to them, and they also bear the personal mark of Cole. Such is art. Its ineffable meaning reaches us on an intuitive, aesthetic level and bears a truth that defies rationality and strict categorization. That, in fact, is one of Romanticism’s insights.

There were many cross-currents within Romanticism, a movement that spanned a century and spread across Europe and to America. The particular beliefs, religious convictions, politics, and philosophical views of those who were a part of the movement varied considerably. Nonetheless, it constituted a distinct movement in history and once you know what to look for, it is easy to spot a Romantic. A particular sensibility and intuition about life guides Romantic thinking and artistic expression. It possesses a certain quality of imagination.

Paradoxically, although Romanticism has helped us to better understand the imagination’s power for conveying truth of a non-rational nature, its moral-spiritual ethos misses the mark, thus tainting the quality of its imaginings (this will be the subject of the third post).

Here, I am going to explore the role of imagination and the period when the concept of the creative imagination burst onto the Western philosophical scene for the first time. This was significant for Western art and philosophy, and should be of especial interest to Christians and Catholics. The West has long been oriented by an intellectualism that has tended to downplay the significance of imagination (in philosophy rather than in practice, at least up until the mid-20th century). The Catholic Church is today suffering from this over-intellectualization, I would argue. The stress on “reason” has made the Church ill-equipped to deal with modernity. Paradoxically, this emphasis on rationality is actually linked to romanticism; they are two sides of the same coin. In both cases, tradition is rejected in favor of abstractionism. The rationalism-romanticism dynamic within Western thinking and also the mind of the Church paved the way to such catastrophes as The Second Vatican Council.

If it is not the intellect but the imagination that gives us our moral sense, as many Romantics believed, we would need to revise current educational philosophies to take this into account; we would need to revisit the value of hideous churches and a “simplified” and rationally-accessible liturgy; we would need to consider the gravity of the effect of what we feed the imagination from literature to film to the aesthetic of the home. All of these things seem to be happening, actually, within traditional circles, where there is an intuitive rejection of the “reasonable” Christianity in favor of the old mystical and beautiful Christianity.

Among Christian and non-Christian conservatives in general, however, there is need for a deeper appreciation of the role of imagination. The Left seems better to appreciate that to control the culture, it is necessary to control the media, the publishing houses, Hollywood, and academia—the institutions that shape our imaginations. Conservatives, historically, have focussed almost myopically on politics in the narrow sense while the Left slips its tentacles into every nook and cranny of the culture. The result is that kindergarteners are being read stories by men in princess dresses while the mothers of these kindergarteners are wage-slaves for companies that, in a heartbeat, would send their jobs off to India in order to increase Earnings Per Share by a quarter of a percent. So tight is the Left’s grip on the imagination that many people see nothing wrong with this situation.

What we would now dub “normie” conservatives have, historically, assumed that teaching the basics of the Christian faith, attending church on Sunday, and keeping out the overtly ideological material is generally sufficient for raising good kids. But what post-modernity and post-Boomer generation reality has taught us is that this is not enough—not nearly enough. The imaginations of young people, even those catechized, weekly-mass attenders, are being formed in large measure by the surrounding anti-Christian culture. Without a major intervention—largely removing children from the mainstream culture and practicing Christianity throughout the week and throughout the home—there is little hope of children keeping, much less passing on, the faith (to say nothing of their future happiness and ability to live life free from dependence on SSRI drugs).

So where does Romanticism come in? The Romantics, beginning with the proto-Romantic thinker (and Catholic) Giambattista Vico, saw the value of imagination and creative expression. The imagination, Vico contended, rather than the rational faculty is responsible for giving us knowledge of truth. This epistemological (“how we can know”) insight was novel. Vico was the first to offer a thoroughgoing (if somewhat unsystematic) philosophy of the role of imagination in our apprehension of reality. Western thinkers since Plato have recognized the power of imagination, but none, to my knowledge, had given it due consideration as a primary source of truth. Rather, the imagination or “fancy” was always taken as a potential (and potent) source of falsehood and illusion. It is the role of reason, Western philosophy has long taught, to correct the excesses and delusions of the imagination.

If Vico is correct, that we apprehend truth and reality by way of the imagination (with reason acting in a secondary role), then there would need to be a shift away from the basic premise that right reasoning corrects wrong thinking. You can’t reason a person out of his or her stance on abortion, for example. It is a function of the imagination, and one’s stance on abortion is going to be tied to his stance on euthanasia, immigration, taxation, the family, children, and more. It all hangs together in the imagination.

Vico’s novel insight about the power of imagination to put us in contact with knowledge of reality provided an epistemological foundation for an aesthetic and philosophical movement that was gaining momentum in Europe: Romanticism. The imagination was being treated, for the first time in Western thought, as a mental faculty capable of connecting human beings with transcendence.

This is something that Christianity has always intuited but did not flesh out philosophically. Christianity’s attempt to rationalize itself in the Early Modern period, I would argue, contributed mightily to its decline in the West. In short, it lost its imaginative appeal.

The momentum for the Romantic movement came in large measure from its hold over the imagination. It was re-enchanting the world with the supernatural, although of the wrong sort. It led to occultism, pantheism, and strange, idiosyncratic interpretations of religion—some of which had pronounced sexual overtones.

The New Age movement that looks to crystals, tarot cards, and the occult for quasi-spiritual experiences draws from a Romantic tap. I would argue that the West’s obsession with yoga also has its origins in the Romantic desire for spirituality—any spirituality, just not traditional Christian spirituality.

Part of the Romantic insight into the imagination came about as a reaction against a literary and aesthetic neoclassicism that had grown rigid and dogmatic. Mimesis, or “imitation” of the masters, had been the prevailing method in the arts, but in this period it could tend toward mere formalism. The neoclassical tradition, at its height, produced some incredible works of art that emphasized harmony, order, proportion, and stressed the beauty of the human form. It often looked to the Greeks and Romans for inspiration.

However, there were strains of the neoclassical tradition that devolved, and the rigid rules it imposed on the arts contributed to the Romantic reaction against it (it should be noted that Neoclassicism itself was a reaction against the earlier romantic excesses of the Rococo and Baroque periods). The rationalistic systematizers among the philosophes only further encouraged a desire among Romantics to fling open the doors of the imagination and to enter into a world that recognizes a reality beyond the visible and empirical.

Romanticism, however, was prone to excesses of its own. Its rebellion against formalism turned, for some Romantics, into wholesale rebellion against standards. Not only art, but all of civilized life was to be tested against the idea of “authenticity.” The weirder and more idiosyncratic, the more “authentic” (and sometimes ghastly). The abiding theme of Romanticism is dream turned nightmare. The movement often vacillated between these two extremes.

The two sides of Romanticism could not be captured better than in the sheer titles of the two paintings, the Pic Nic Party and The Edge of Doom:

Unfortunately, the response to Romantic excesses, often by conservatives of various stripes, has been, on the whole, to reject the imagination as a source of truth and to turn to reason as the antidote. If the creative imagination leads to the insanity of the French Revolution and indulgent and grotesque art and literature, then the restraining force of reason is what is needed, the anti-romantics argue.

Literary scholar and Harvard professor Irving Babbitt saw clearly the virtue of Romanticism’s imaginative capacity, but he also saw its inclination toward an ethical-spiritual decadence. Moreover, he recognized that the romantic imagination must be countered not by reason but by the rightly formed imagination. The world is split, Babbitt argued, between two different types of imagination, the romantic imagination and the moral imagination.

The third post in this series on Romanticism will delve into this idea of quality of imagination and in particular, the quality of the romantic imagination.

See Part III of this series here.

I believe it was Einstein who said that 'Imagination is more important than knowledge.'

This is an excellent essay, on a topic that is not sufficiently discussed. Romanticism is probably the most ambivalent cultural movement in Christian history—there seems to be so much good hopelessly entangled with so much bad that one hardly knows what to think about it in the end. Even for secular scholars just trying to understand Romanticism from a philosophical or aesthetic standpoint, contradictions abound. A hundred years ago, the philosopher Arthur Lovejoy gave an influential lecture in which he basically said that no one can really make sense of Romanticism: “The word ‘romantic’ has come to mean so many things that, by itself, it means nothing. It has ceased to perform the function of a verbal sign. When a man is asked, as I have had the honor of being asked, to discuss Romanticism, it is impossible to know what ideas or tendencies he is to talk about.” He offers this (somewhat exaggerated) conclusion with a note of despair, since “philosophers, in spite of a popular belief to the contrary, are persons who suffer from a morbid solicitude to know precisely what they are talking about.”

In any case, I really like the way you’ve attempted to parse out the nature and implications of the movement from a traditional Christian perspective. This needs to be done because the influence of Romanticism, sometimes beneficial and sometimes baleful, is still with us. But to end on a positive note, we must thank the Romantics for defending the imagination—or what might be more accurately termed, in their case, the “fullness of the interior life”—from the onslaught of rationalism and empiricism. Keats captures it memorably in “Lamia,” where by “philosophy” he means something closer to what we call “science”:

...Do not all charms fly

At the mere touch of cold philosophy?

There was an awful rainbow once in heaven:

We know her woof, her texture; she is given

In the dull catalogue of common things.

Philosophy will clip an Angel’s wings,

Conquer all mysteries by rule and line,

Empty the haunted air, and gnomed mine—

Unweave a rainbow, as it erewhile made

The tender-person’d Lamia melt into a shade.