The Unadjusted Child: A New Hero for America

Why we shouldn't be raising normies and how reading bad books can be a good thing

We are in the midst of “an ecstasy of universal voluntary lobotomy,” said Peter Viereck, one of the founders of intellectual conservatism in the twentieth century. Viereck argued in his book The Unadjusted Man: A New Hero for Americans (1956) that most people in American exercise an automatic self-censorship, a “complacent kind of surrender.” He calls these people “overadjusted”—what we might call “normies” in today’s parlance.

The Overadjusted Man has “an abnormal desire for normalcy” as an end in itself. He is loathe to question the authority of his secular overloads. He would rather not ruffle feathers, preferring to remain polite in a bourgeois sort of way, even in the face of the most egregious violations of his liberty. Had Viereck been alive to experience the orgy of hypochondria in 2020, he would say that his book did not go far enough. How desperately we need people who will refuse to succumb to the mass hysteria that, from climate change to so-called health emergencies, spreads like a California wildfire among the overadjusted American populace.

The unadjusted man, Viereck says, resists the procrustean urges of the day and conforms himself instead to a higher, timeless standard. This conformity results in a desire to conserve that which is best and “to be stubbornly unadjusted toward the mechanized, depersonalized bustle outside.” Viereck didn’t even know about Klaus Schwab or AI. It is precisely this unadjusted man who is “the final, irreducible pebble that sabotages the omnipotence of even the smoothest-running machine.”

In an age of aggressive thought-control, godlessness, and groupthink that would make the Soviets blush, it is our duty to rear unadjusted children. Nor should they be maladjusted, as Viereck points out, which would result in misanthropy or a sort of antinomianism. They ought to be adjusted “to the ages,” Viereck says, not “to the age.”

A recent incident in my home helped me to understand one way in which we can encourage this “unadjustedness” in our children. It happened that my son was reading a book about the California Gold Rush. In it was a passage that claimed that the Native Americans were all but wiped out by the Gold Rush, as if ordinary men and women prospecting for gold killed natives for sport. Professors of history at our illustrious universities would no-doubt be vigorously nodding their heads in assent while tsking, but the rest of us will probably pause at such a sweeping assertion.

I said, “Um, I don’t think that’s true. Let’s ask Dad.” I then read it to my husband, who told my son that the book didn’t get it quite right. He gave a short answer appropriate for a 7 year-old.

At first I was a little dismayed at myself for letting one of these pseudo-histories squeak through the ironclad gates of my home library. But then I realized that what happened was actually a good thing. It demonstrated to my son that books can be wrong, while at the same time reinforcing that his parents can arbitrate the claims of books—that we use our knowledge of history to assess the truth of something we see, experience, or read.

Bound and illustrated, shelved at the library or the bookstore, books can give the impression to little ones (even adults) of being “official,” written by “experts,” and indisputable. When our children see that we do not accept uncritically anything we read or hear or see, they, too, will take a critical approach to what they are told.

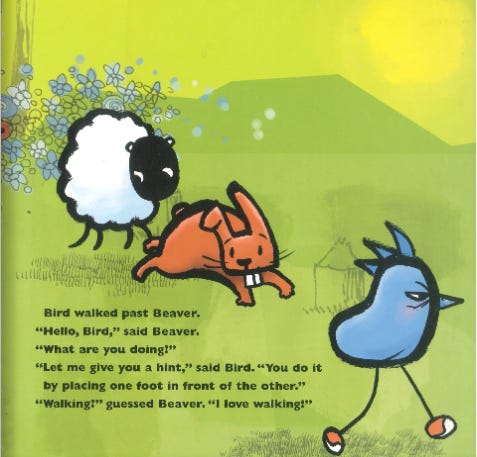

In an earlier post (the 8 worst books for your young child’s imagination) I recalled reading Grumpy Bird, a “book about anger,” to my young child. Before I could properly vet this story (how bad could a board book about anger be?), my son was already sitting down to have me read it.

In sum: a bird wakes up inexplicably angry one day. As he trots past his friends, he hurls snide, sarcastic remarks at them, yet they all decide to walk along with him. By the end, his friends are singing and dancing for him, and Grumpy Bird is cheered.

In my usual blunt fashion, I told my son that this book is terrible and we aren’t reading it anymore. “Why not?” Because it tells us lies, I said. “How does it lie?” he asks. What do you think would happen, I ask him, if you woke up and behaved as that bird does? Would your friends sing and dance and make snacks for you? No, he says. Would anyone want to be around you? No, he says. Would you want to be around a person acting that way? No, he says. So it’s lying to us, I tell him. That book is not telling us the truth about how the animals would have behaved.

Note that the fact of talking animals was never problematic or part of the lie of the book. That’s something we’re all easily able to accept. Of course animals can talk and dance and make snacks. As the august George MacDonald observed, a man may not, for any purpose, turn the laws of the moral world upside down. “The laws of the spirit of man must hold, alike in this world and in any world he may invent.”

Grumpy Bird lies because it makes us think that we can be as mean as we want and everyone will still be nice to us—maybe even extra nice. But this is not how life works. We must take responsibility for our own actions. Children must learn the morals laws of our world. To present their imaginations with stories that teach them to be less like the saints and heroes and more like the Willy Wonka children, is a crime. This is what Grumpy Bird does for your toddler.

But this is not a post about Grumpy Bird. It is about one small way to help encourage your child to be “unadjusted” to the sewage coming out of the mainstream cultural pipelines, and to question the people or sources who push lies.

If your children must be in public school, it is good for them to know that they can and ought to question the teacher, especially if he or she says something that doesn’t sound right or seem true. It is good for them to know that textbooks are written by mere human beings, and human beings err.

This challenge of authority, of course, must be done in the right way, at the right time, and for the right reasons. It is an art learned over time, and best acquired in the home under the gentle, loving care of parents. Taking the opportunity to explain why a book lies or doesn’t get the truth quite right can be the first step in helping a child to understand this art of criticism and discrimination. It can help a child to prepare for the difficult task of resisting the nearly ubiquitous “voluntary cultural thought-control more insidious than the coercive political kind.”

Part of the task of building up Christendom in an age that hates Christ involves a tearing-down by exposing certain lies (never risk your child’s innocence with a book that is really bad; here I am simply advising allowing the occasional reading of an Angry Birds type book or an ill-informed/woke “history”). The other, more significant part, involves a building-up of the moral and historical imagination. The child who has been nourished on books that teach true history and books that spark the moral imagination will readily learn this art of discrimination because he will know and love truth. It will serve him for his entire life.

Awwww Viereck is my favorite and I loved this little nod to him. Nicely written. I believe being overadjusted is The chief danger of our American culture. E we love to think of ourselves as ruggedly individualistic but there are fewer brave iconoclasts than the age requires. So many people who just go along to get along, at any cost. There’s a way to disagree and yet remain Christian and civil.