The Liturgical Movement that is Needed

It must be furnished from the wardrobe of the moral imagination.

A merry Christmas season and a happy start of 2025!

The spirit of a gentleman and the spirit of religion are the two principles that gave Europe its erstwhile culture of chivalry, so said Edmund Burke.

A well-respected political philosopher and dear friend told me that a major revival of mind and imagination is needed for a lasting cultural renewal. “This is going to be indistinguishable from a liturgical movement,” he said.

He meant “liturgical” in the broader sense, not the liturgy at mass or even “liturgical living” as it is understood on the Catholic internet. Liturgical in a Burkean sense. Burke, the great conservative and anti-revolutionary thinker of the eighteenth century, propounds a liturgical approach to all of life. The little rituals, obeisances, courtesies, intentional pauses, graces, mortifications, politeness, and in general, mannerliness, Burke believes, make us human and make this world a humane place to live.

The world “liturgy” comes from the Greek and originally meant “public duty” or “public office.” It transformed to have an exclusively religious meaning in reference to the ordering and ritual of Christian worship. As of late, many are realizing the importance of “liturgical living” beyond the confines of the mass or divine liturgy. The Catholic internet is always abuzz with what crafts or baking ideas to do with our kids to honor a particular feast day or liturgical season.

Burke’s philosophy of the necessity of a “liturgical” approach to life, as this professor has repeatedly said, means that we ought to act as if something really important is going on, as if this life is serious business—which it is.

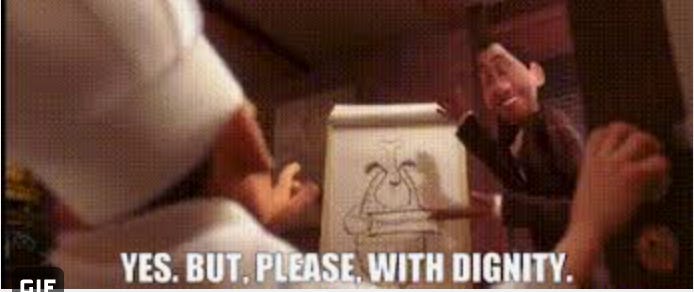

There was a certain imaginative disposition in Christian Europe which compelled folks to behave as if life and people mattered. Honoring a person’s rank with a particular salutation—“sir,” “madam,” “your highness,” “your honor”—bestowed that dignity that today we hear so much about but hardly see acted upon. Showing deference to one’s elders and betters was not degrading to those “underneath” but lifted the entire social edifice from the bottom up, Burke believed.

This system “of opinion and sentiment”—based in the collective imagination—lent gravity and dignity to the life of commoner and king alike. “It was this which, without confounding ranks, had produced a noble equality and handed it down through all the gradations of social life. It was this opinion which mitigated kings into companions and raised private men to be fellows with kings,” Burke wrote in his anti-revolutionary treatise of 1790, Reflections on the Revolution in France.

This ancient chivalry, Burke said, had a power to subdue, to get people to submit to what was right without the full force of the law coming down upon them. “[It] obliged sovereigns to submit to the soft collar of social esteem, compelled stern authority to submit to elegance, and gave a domination, vanquisher of laws, to be subdued by manners.” It is the dissolution of this culture of manners, a culture of universal liturgical living, that has given rise to the litigious, over-regulated, surveillance state that we now find ourselves in.

Social graces once lubricated our interactions and made even enemies act kindly toward one another publicly. These “pleasing illusions,” in Burke’s words, made life in society not only bearable but happy, even for the lowly.

If we returned to a culture in which, as a rule, children said “sir” and “madame,” abortion would become the unthinkable crime that it is; marriage would return to its formerly-held place of sanctity; children would be protected from predators who would return to the shadows, knowing that neither the law nor the culture would protect them; public schools could once again be places of learning since teachers would no longer spend the bulk of their time on discipline issues.

Don’t get me wrong. I do not think that artificially forcing this one point of civility would radically transform a rotten and decadent culture. I am positing that this seemingly small showing of respect is a sign of a culture’s entire imaginative understanding of life, which is premised on the acceptance of a fundamental hierarchical ordering that begins with God at the head and descends down to the animals (who even would benefit from a culture in which children respectfully address their elders). To see such respect accorded to one another, including the children who will one day inherit the culture, would indicate that people believe in an order that is not of their making and over which they have no control.

Narcissism and anxiety could never plague such a society, for looking outside of oneself and respecting the cosmic order would be the rule from birth. Obsessing over “finding oneself” and “finding meaning” would be outside of the realm of imaginative possibility. The rails have been laid. Life’s parameters are fixed. It is left to each person to work out his or her salvation within the context of a chosen vocation.

Returning to a culture in which children respectfully address their elders would have to happen as a result of a collective imaginative shift. First, people would have to believe the sorts of things that are said in corporate mission statements and UN declarations about the dignity of each individual—which really is the product of Christian civility without the “lived experience” behind it, hence why human rights atrocities proliferate even as nations and corporations issue yet further statements about humanity’s rights.

Burke believed that the morals and manners of pre-revolutionary Europe humanized us and dignified us. The Enlightenment luminaries derided as unnecessary and artificial the social conventions that accorded respect to persons and to God, such as respectful salutations, crossing oneself when passing a Church, and honoring our elders. These customs fell out of fashion as the rationalists and utilitarians began to have their way, first in the culture and then in politics.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau, for his part, believed that we would do well to return to our “natural” noble savage nature, leaving behind these superadded customs of “respect” that merely hide who we really are.

Burke agreed that these customs were artificial, in a certain sense. Pleasantries and decorum, which Burke called “the decent drapery of life,” indeed covered our naked selves. But this is a very good thing, Burke says. For without such manners, we will see how cruel and savage life can really be. It certainly won’t be anything like Rousseau’s fantastical state of nature in which we drink from a stream and rest under the shade of a fig tree. It will be more akin to the Hobbesian bellum omnia contra omnes, the war of all against all.

It is no surprise that in revolutionary France the guillotine was wheeled out alongside the mandate to abandon the use of “monsieur” and “madame.” The same happened in Russia after the Bolshevik revolution. People were forced at gunpoint to use “comrade” over former titles of distinction. The gruesome and grotesque always accompanies the degradation of manners.

This great revolutionary leveling of humanity along the lines of the equalitarian “citizen” or “comrade” has tracked pretty well with the rise in barbarism. Burke predicted as much:

“[O]n this scheme of things, a king is but a man, a queen is but a woman; a woman is but an animal, and an animal not of the highest order. All homage paid to the sex in general as such, and without distinct views, is to be regarded as romance and folly.”

In other words, if we do not experience, at the level of imagination, the conviction that people are important and inviolable, then we will not act as if they are. Life plays out as a result of imagination. Women will not be treated as worthy of chivalric behavior if we do not believe that men and women are distinct beings, each with their own noble ends—we can see Burke’s prescience. The sexual revolution brought the ideas of the French Revolution to their full conclusion, from the degradation of women (and men) to the normalization and even celebration of abortion—“a baby is but a fetus.”

As for a broader liturgical movement that could renew the culture, the virtue of gentlemanliness and the revival of religion, as Burke points out, are foundational.

The secular culture has done away almost entirely with the virtue of gentlemanliness, which is predicated on recognizing natural distinctions between the sexes. The sexual revolution has created an animosity between men and women, making them distrustful of one another and seeing each other as means to momentary gratification. The fourth-wave of feminism, or whatever we are in now, has confused gender roles entirely, creating a culture of effeminacy that is degrading to men and confusing to women. Women are encouraged to suppress their natural inclination toward motherhood in favor of climbing the corporate ladder, while men are taught to repress their masculinity and don the “pink p*ssyhat.” Surgeries and chemicals are now employed in the social quest to remake the sexes and to achieve finally a universal androgyny.

Gentlemanliness, on the other hand, would revive the romance of marriage and return to the imaginations of young women a longing for happy domestic life, shorn of any delusions about first finding oneself or pursuing a career over and above a family. Children would return to the care of their mother and the protection of a father who provides for them. This would require a new imaginative understanding of the role of the sexes—one rooted in a traditional division of labor.

I see positive steps in this direction with single-sex private schools popping up around the country. Having largely abandoned single-sex education as “sexist” or whatever the boomers decided, we are again realizing its benefits. Education is not one-size-fits-all, and it is often the boys who suffer most under today’s public education regime. As it turns out, sitting in desks for 6 hours a day is not compatible with testosterone.

Single-sex education, I believe, will have the paradoxical effect of reuniting the sexes in friendship and amicability, ultimately setting the stage for healthy relationships and stable marriages. Boys will learn the art of gentlemanliness in a culture of (it goes without saying, healthy) masculinity. Women will re-learn the art of femininity that the feminist hysteria would all but destroy.

Part of rebuilding a culture of gentlemanliness will be a return to seriousness, to acting as if this life matters (which is revealed in children using “Mr.” or “Mrs.”, for example).

I see many positive signs in the Christian counter-culture. Small and medium-sized Christian publishing houses, for example, are returning seriousness to the faith and to education. Many parents instinctively dislike the twaddle and books-based-on-tv-shows that are on offer at the major booksellers and the local library. Even many religious books that are for children are cartoony and betray a lack of seriousness that we probably ought not to convey to our children when we are, in fact, imparting to them something of the utmost seriousness and importance.

St. Augustine Academy Press is one example of this revival. A homeschooling mom (of course!) started this enterprise when she realized that some of the best (and beautifully illustrated) religious books were out of print, and could be brought back without needing to deal with copyright issues.

Yesterday’s Classics is another press that has brought back many, many great history and literary works (at an affordable price) that we use for homeschooling. Riverbend Press similarly has brought back (in beautifully bound editions) formerly out-of-print books that Charlotte Mason used with her students. I’ve noticed that well-known publishers such as TAN and Sophia Press are doing similar things. I know there are many, many more right now.

Contrast the offerings of these wonderful publishers with the wider secular culture’s cheapening and commercializing of the liturgical life—the order, ritual, and all that is right and proper in it. Take, for example, the “Easter” books displayed at the local library (if they decide to make room next to the sprawling Ramadan display, that is—which mine did not last year). They are all about “Hoppy the bunny” and “springtime celebrations.” Readers of this Substack no doubt try to avoid that kind of secular thing, but consider this: Easter has transformed in the popular imagination from a very serious affair that occurs on the heals of a sustained period of fasting and the holiest, most somber weak of the entire liturgical year into a frivolous, meaningless affair of bunnies and pastels. This is the destruction of the seriousness and dignity of life.

None of this is to say that joy and laughter have no place in the liturgical life, which is necessarily serious. On the contrary, joy and mirth are a part of seriousness and an integral part of the liturgical life.

The liturgical life is about proportion. The period of Lent (and also Advent) gives us a period of sobriety, fasting, and reflection in which to deepen one’s spiritual life and better one’s practical life. This is followed by a needed celebration. And it is all modeled after the life of Christ.

As for the spirit of religion that Burke identifies as foundational for civilization, for it to have the effect that Burke lauds, it must be serious. For what is more serious than the liturgy of the Church? But delving into the liturgical crisis in Christianity will require another post. Part II of this post is forthcoming.

Thank you, thank you, thank you for this!!! I love that you are advocating for a return to addressing people as "Mr." and "Mrs." For years, even before I knew it had so much meaning behind it, I have been wishing we could still be formal in society. That is one of the things I love at my TLM parish -- that all of us young people are expected to address our elders by title and last name. I try to incorporate that into my life away from the parish, but it is often hard because most of my elders act so friendly and only give me their first name. I don't mean that they shouldn't be friendly, but they are so in a way that would make me addressing them as "Mr." or "Mrs." seem out-of-place. I wish we could incorporate that, too, among the youth, at least when it comes to young men and young women interacting with each other. I have yet to hear someone seriously address me as "Miss"! I'm really looking forward to it.

I am a big proponent of this expansive view of "liturgy" applied as a lifestyle, rather than a narrow to-do list. I would argue though that some of the “secular” seasonally-themed children’s books do have a place alongside (not in place of) books that focus on liturgical seasons. Kids learn that the natural as well as the Church year is cyclical and liturgical in its own way, and that their favorite characters are bound by the same seasons. In my opinion if I'm checking out books about construction vehicles anyway, it's an added bonus to have them relate to the seasonal rhythms at even a surface level–and some of them do go far beyond the surface! (Although if there's a book out there about excavators and the religious meaning of Easter, count me in).