The Brilliance of Metaphor and Why the Left Can’t Meme

And nature study, Charlotte Mason, and the imagination

“To inquire into what God has made is the main function of the imagination” —George MacDonald

George MacDonald, the inimitable author of fairytale of the Victorian era, declared, “all that moves in the mind is symbolized in Nature.” MacDonald well understood the power of imagination. The imagination, he said, gives the scientist his questions for inquiry just as it develops events into a history. It is the force that gathers, synthesizes, and creates.

Time spent in nature is indispensable to the cultivation of the moral imagination. I do not mean that Mother Nature will yield mystical, esoteric knowledge to the sensitive Romantic soul. Nor that uniting our feelings with Nature will grant us access to the unmediated truth of existence, which, according to the Romantic, need not involve a personal God.

Rather, the Christian relationship with nature is one that is ordered toward God the Creator. It allows us glimpses of eternal truth, of the manifold beauty of existence. In so doing, it inspires the poetical mode of thought. Charlotte Mason:

“Get the children to look well at some patch of landscape, and then to shut their eyes and call up the picture before them; if any bit of it is blurred, they had better look again. When they have a perfect image before their eyes, let them say what they see. Thus: ‘I see a pond; it is shallow on this side, but deep on the other; trees come to the water’s edge on that side, and you can see their green leaves and branches so plainly in the water that you would think there was a wood underneath. Almost touching the trees in the water is a bit of blue sky with a soft white cloud . . . etc.”

Observing the natural world, Mason said, creates a foundation for the language arts. Playing a game of mental “picture painting” with her children, a mother is able to help lay this foundation. Describing what we see “fully and in detail” will help to develop the habit of paying close attention. Begin able to communicate what we see will refine our own understanding and will force us to reach for the right words in order to give the clearest, richest description. The mother describing a landscape, for example, will serve as a model. “[A]ny graceful fanciful touch which [a mother] throws into her descriptions will be reproduced with variations in [her children’s].”

The natural language in which we will express ourselves, Mason suggests, will be poetical. Nor should we spoil “the simplicity, the objective character of the child’s enjoyment,” Mason says, “by treating his little descriptions as feats of cleverness to be repeated to his father or to visitors . . . though the child should show himself a born poet.” In other words, describing the beauties of the natural world will elicit poetical language even from children, and especially when their mothers set the tone with rich, lyrical language.

This pedagogical activity is fun for children, but as Mason says, it is also taxing, as “it involves some strain on the attention.” Thomas Carlyle, whom MacDonald cites, said in Past and Present, “The coldest word was once a glowing new metaphor and bold questionable originality. Thy very attention, does it not mean an attentio, a stretching-to?” Our attention, our “stretching-to,” connects our imagination with nature in an immediate way. Doing this repeatedly builds an imagination that can make use of metaphor—all the better when those metaphors are “glowing new”!

The great 18th century philosopher Giambattista Vico said that metaphor is the basis of wisdom. In Vico’s magnum opus, The New Science, he argues that the first peoples were born poets, rich in imagination and poor in the power of ratiocination. His understanding of the ancient role of fable was groundbreaking and influenced the Romantic movement. Vico says that metaphor is at the foundation of the “poetic logic” of the ancients. That is, they naturally thought concretely, not abstractly, and metaphor came natural to them as a manner of communicating. Metaphor, Vico said, is “the most luminous and therefore the most necessary and frequent” of the first poetical tropes. Now, it is only with difficulty that we modern rationalists can recover this type of thinking (for reference, rationalism reigned by the time of Plato, according to Vico’s philosophy of history).

In my estimation, the most effective (and funniest) writers are those who have command over the use of metaphor. Peachy Keenan comes to mind. Her writing can be gut-wrenchingly hilarious (like my use of metaphor there?) because of her deft use of metaphor. This skill is something that the more artistically minded possess to a greater degree than other folk, and I believe this is because of their disposition toward imaginative, concrete thinking.

Aristotle says in The Rhetoric that “metaphor especially has clarity and sweetness and strangeness,” and further, that “its use cannot be learned from anyone else.” It is an art, and one that enchants by its novelty and the rich, immediate images that it forms in our imaginations.

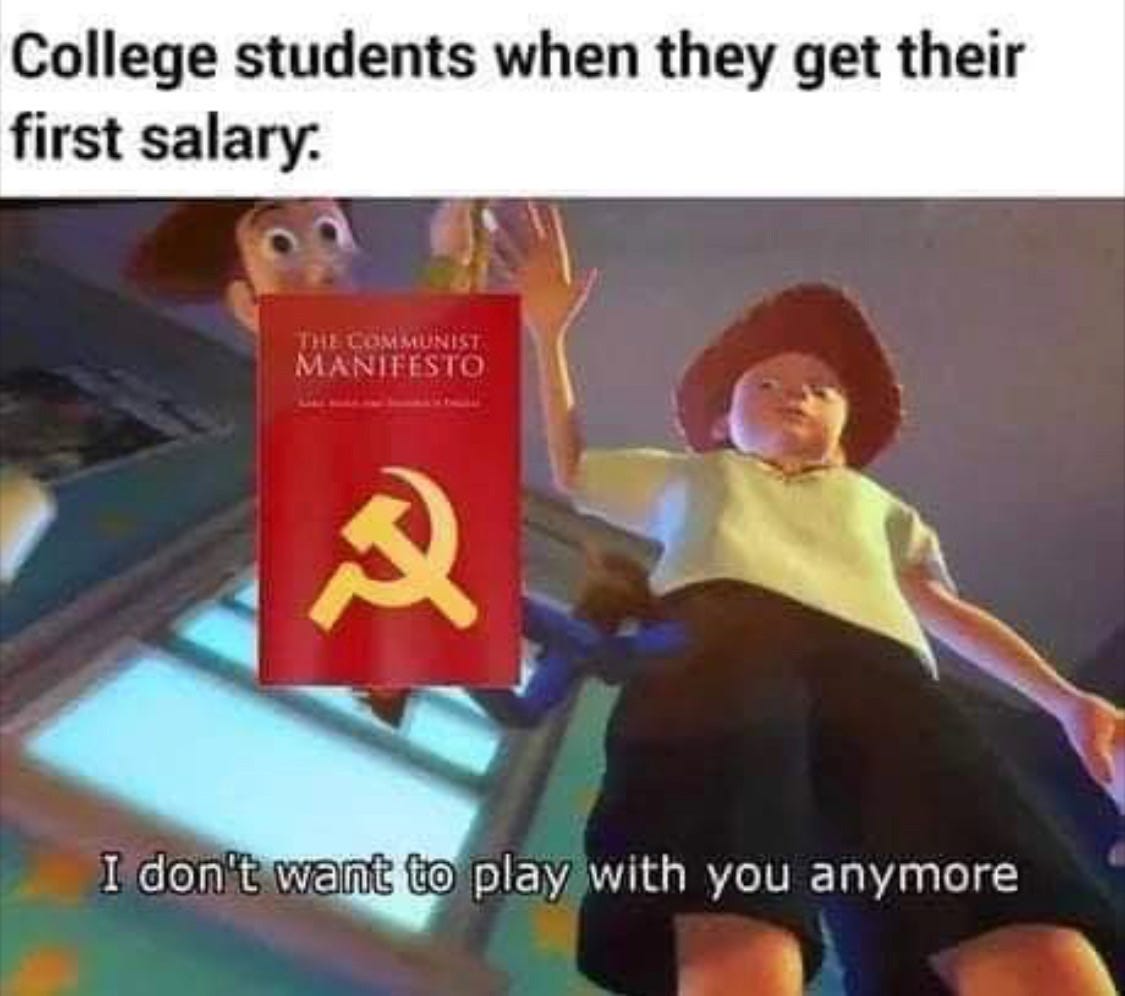

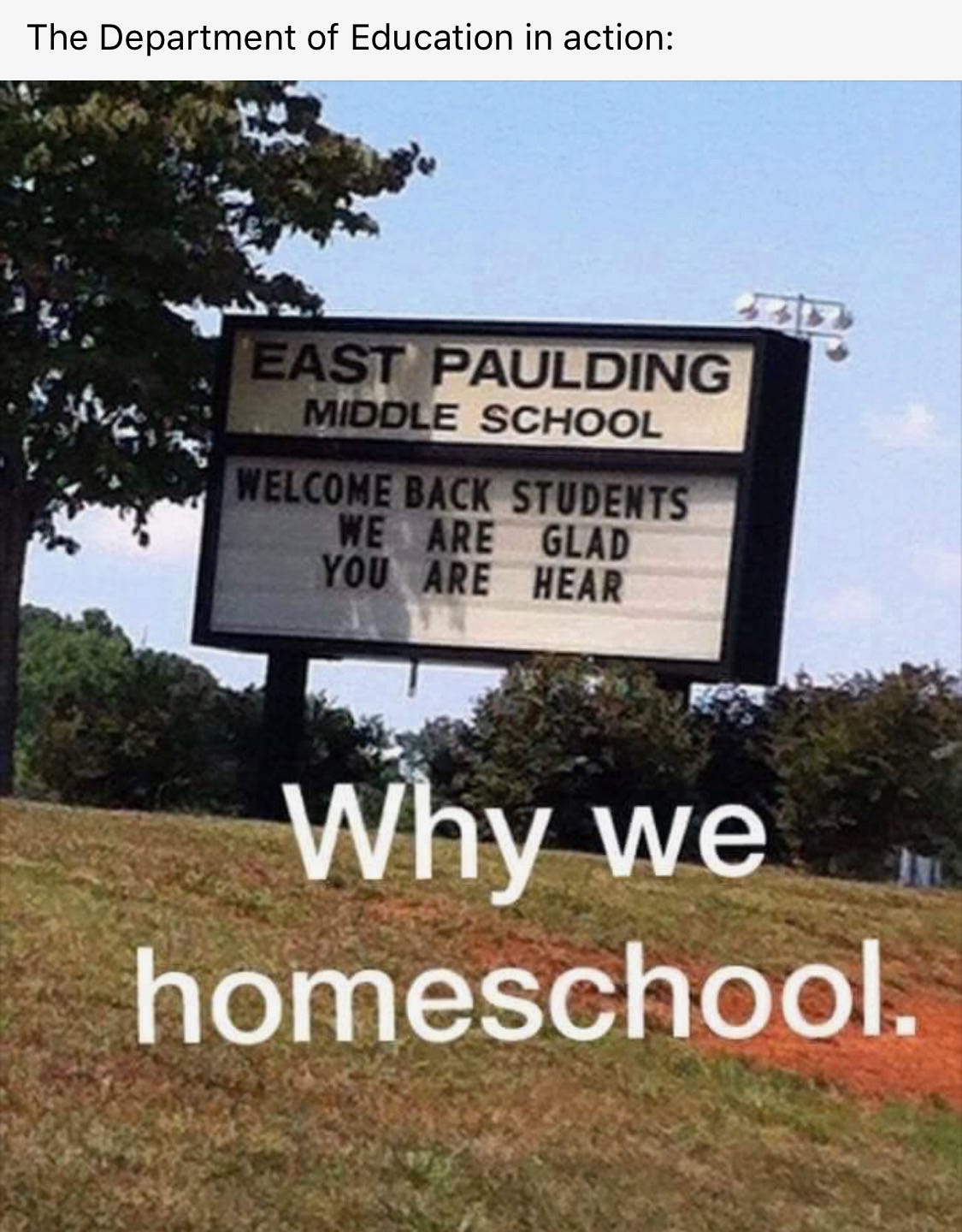

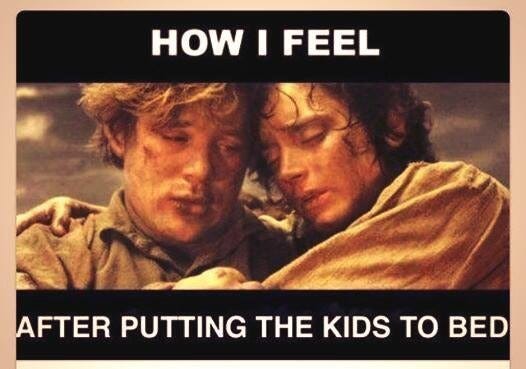

This is why the Left can’t meme. Memes are visual metaphors, so to speak. In one image with a single caption, the significance of a complex cultural phenomenon can be captured (see Meme Appendix below). It’s remarkable. And I think that it is no overstatement to say that memes helped Donald Trump to win the presidency—twice. These little visual chunks of culture can be devastating when deployed against one’s enemies.

The meme of the “liberal meme” perfectly captures the problem for the Left:

When reality needs to be interpreted and explained, then it’s not reality. Modern left-wing politics rely on “the narrative,”which is in constant need of reinforcement and longwinded explanation, as it is ideological rather than based in truth and reality. Leftism resists the poetical mode of communication that cuts straight to the truth. This also happens to be why left-leaning television shows and comedians aren’t funny. They can’t convey truth in the visceral, immediate way that causes us to laugh. Humor is tied to reality.

Nature is a particularly rich source of metaphors. Christ’s parables come from the natural world. Christ says that he is “the true vine” (John 15:5). He teaches about the spiritual life with the image of a fig tree (Luke 13:6). He compares the Kingdom of Heaven to a mustard seed (Matthew 13:31; Mark 4:30). He teaches much through images of sowing and reaping, planting and harvesting.

Vigen Guroian in his wonderful volume Tending the Heart of Virtue: How Classic Stories Awaken a Child’s Moral Imagination, observes, “That which is ‘outside’ of us is the necessary precondition for understanding ourselves inwardly.” Guroian mentions the importance of experiencing nature for understanding reality and having the language to describe reality. The “world in its wholeness.” Guroian says, is revealed in the intimate particulars of the natural world.

“When we put into words [the] experience of the external world with its forms and images and relate that to our inner experience, our humanity in all its depth and complexity of meaning flowers and is unveiled.” The outward reflects the inward and shines light on it.

Vico, for his part, mentions that in all languages, a great number of metaphors are drawn from the parts of the human body and its senses and passions. Think of the head indicating the top or beginning of something; the eye of a needle or potato or hurricane; mouth as any opening; the tongue of a shoe; the teeth of a comb; the hands of a clock; the belly of a sail; the vein of a mineral; the bowels of the earth; etc. At the same time, the natural world can stand for something that is inside of us.“What would we do without the lion to remind us of the nobility that belongs to our nature or the owl for the wisdom into which we must mature as human beings?” Guroian asks.

The world, says MacDonald in very Burkean fashion, is “an inexhaustible wardrobe for the clothing of human thought.” Life can seem beautiful or ugly depending on our frame of mind, and that frame of mind is indistinguishable from the imagination. It is our imagination that creates our sense of reality and whether we find in life beauty or ugliness, indeed whether we create beauty or ugliness.

Meme Appendix, for your enjoyment, dear reader (and a big thank-you to my dear friend L., wife of a hard-working meme harvester):

So much of the Left and its arguments lack depth. Very difficult to gather their attention long enough to explain plain truth to them. This is why nothing from the Left has any enduring qualities. There is nothing there to sustain its thinking. It's a kind of teetering Jenga tower.

“Observing the natural world, Mason said, creates a foundation for the language arts. Playing a game of mental “picture painting” with her children, a mother is able to help lay this foundation. Describing what we see “fully and in detail” will help to develop the habit of paying close attention. Begin able to communicate what we see will refine our own understanding and will force us to reach for the right words in order to give the clearest, richest description.“

This rings very true for me. When I taught writing to middle schoolers, I remember having such a hard time getting students to write anything that was not mind numbingly boring when we used the 5 paragraph structure. When we got to the descriptive writing section of the writing course and they had to write about what Mason describes here, their writing improved leaps and bounds. They started using metaphors and interesting words etc.

I had to follow the curriculum, so I couldn’t just throw out the longer essays, but I was amazed by how much descriptive writing/detailed observation from nature study helped them articulate themselves.