Reality through a Veil of Illusion

Tailgating for the TLM Easter Vigil and the children’s stories of Caryll Houselander

I was raised in the modern secular culture of materialism and empiricism with a sprinkling of Catholicism on the side. It came as a genuine surprise to me when I learned from my public school English teacher that Christ is really present in the Eucharist. I thought of demons as symbolic realities rather than actual forces in the world. I never gave a thought of my guardian angel until my “reversion” in my twenties. And it was not until I read a well-known (in Russia, anyway) Orthodox book called Everyday Saints and other Stories by Metropolitan Tikhon that I began really to appreciate the spiritual dimension of existence. This book struck my imagination in a way that other experiences had not.

How do we know that there is a spiritual reality? Most of us will not be graced with an apparition of Our Lady or a vision of Our Lord. Will we recognize a miracle granted? Can we see the workings of grace in our life? Are we aware of the Real Presence and the reality of Heaven, Hell, demons, angels?

How to ensure that we bring up our children to experience the higher reality of Christian life?

What has probably come by intuition to those raised in practicing Catholic homes, has come to me (very imperfectly, I should add) through countless hours of research during and after a postdoc, reading Catholic mom blogs on the internet, trying to dredge up knowledge of traditions and “liturgical living,” talking to a devoutly Catholic family member who has been a guiding light, talking with our priest, and praying for help—all with the help of my husband.

I came to the conclusion that the answer to how to impart the higher reality of life—meaning Christian truth about angels, demons, the Real Presence, Heaven, Hell, the saints, the Resurrection—to my children (and to myself, for that matter) lies in liturgy, literature, song, and nature. Part of our decision to homeschool came about because we realized that religious education could not be bracketed as a side “subject” or something we dwell on merely on Sundays. Christianity must permeate everything. This required a radical reorientation on my part, as I had been a product of this bracketed Christianity. I think that the boomer generation was able to live off of the pre-Vatican II spirituality that still lingered on, but by the 1980s and 1990s, there were mere fumes of the traditional faith left, and these were not enough to sustain the next generations. Sunday mass and catechism class, otherwise enveloped in a culture of materialism, scientism, and sentimental humanitarianism, are not enough.

Millennials and later generations seem to fall into one of two camps: those who have fallen away from traditional Christianity entirely and those who are having or who have had a “reversion” or conversion to the faith and have dived headlong into orthodox Christianity. The good news is that I am genuinely optimistic that we will see a real resurgence of traditional Christianity that will continue to grow long after I am gone. The explosion in homeschooling is one sign that times are a changin’. Another good sign is the explosion in traditionalism and demand for the old Mass (and also conversions to Orthodoxy). These are signs that the culture of materialism and humanitarianism, rooted in romantic sentimentalism and delusion, are becoming exhausted and being revealed as empty.

I’ll give just one anecdote to support this thesis: on Good Friday at the FSSP parish in Los Angeles that celebrates exclusively the traditional Latin Mass was packed by 1 pm for the Stations of the Cross and the 3 pm liturgy. Not a parking space could be found, and people were pouring outside of the church. For the Easter vigil, which was set for 8 pm, one family arrived at 4:30 pm to get a pew. By 7 pm all seats in the church were gone.

People are starved for tradition. Why tradition? Because tradition taps into the wisdom not of a few innovators or “experts” but the wisdom of the ages, of the countless people and of saints and doctors of the Church who have participated in and benefited from a particular way of life and of expression. The past five years have shown us nothing if not that “experts” cannot be trusted. The movement toward homeschooling, homesteading (real or imaginary), reviving real and local food sources, building up the local religious community, living by the liturgical seasons rather than industrial time, all show that people are bucking the noxious trends that the 20th century foisted upon us.

A friend recently recommended a cookbook, which is actually part science, part philosophy, and also recipes, called Nourishing Traditions: The Cookbook that Challenges Politically Correct Nutrition and the Diet Dictocrats.

This book would find a happy home among both hippies and rad trads alike, as it brings to light the scientific backing of traditional dietary wisdom. In brief, we can all rest assured knowing that eating real foods like butter, cream, animal protein, raw milk, and whole foods is what’s best. Leave behind the pseudo-science of the 1990s about low-fat and high-sugar diets and the various and sundry gnostic fad diets, and just eat what people ate prior to the 20th century. We would probably do well to heed this advice on religious matters, too. Let’s just go ahead and bracket the twentieth-century and leave behind all of its noxious ideologies whether it be dietary, ecclesiastical, or political.

But, I digress. What I’d like to explore is how we impart the faith. I dwell on children’s literature here at The Christian Imagination because literature uniquely taps into the imagination, especially young and impressionable minds. The stories children read when they are very young will shape their imaginations in ineffable and untold ways. These stories teach children about reality and about the world. Children should read books, but they should not read just any books. In fact, we ought to be very careful about what we read to them because this is part of their early experience of culture, and we need to make sure that we give them the very best and also the truth.

Paradoxically (or so it may seem to us moderns), we get at the truth through illusion. By illusion I do not mean trickery or magic or lies. I mean fictional stories that convey the truth of existence in a way that we finite humans can grasp and appreciate, however fleetingly or tenuously. Christ demonstrates this epistemological truth by speaking in parables. “For now we see through a glass, darkly,” Saint Paul says. We must get at the truth of the higher reality of His Kingdom obliquely.

Story and song and all lyrical learning transpose us imaginatively to a plane outside of ordinary, material existence. But this power of story and of imagination is double-edged. The imagination can take us to a “land of chimeras,” as Rousseau was wont to do, or it can give us a glimpse of the eternal. Plato well understood the power of imagination. As he crafted his ideal city, the Kallipolis, he took care to ensure the proper imaginative training of the city’s guardians, keeping out story and song that would malform their minds. However, Plato believed that right reasoning was the corrective. In fact, reason is rather impotent in the face of powerful imaginative allures. Only the rightly formed imagination can resist the temptations of competing desires that strike the fancy of the imagination.

The main competitor that Christianity faces in modernity is not materialism or even scientism but, as I have argued, romanticism. The romantic imagination is a formidable opponent because it indulges what our lower selves would like to be the truth: that life can be easy. It eschews limitations and discipline in favor of expansive feeling and sentiment. But this feeling lacks a center to hold it, and it can quickly grow into desire without restraint.

The moral imagination is the stronghold that must be built up in children so that they can withstand the onslaught of nihilism, secularism, feminism, and the myriad ideologies, attractively garbed, that will be thrown their way. Think of every fairytale, song, poem, and play in nature as one more brick added to their fortress.

Excellent and well-made sturdy bricks can be found in abundance in the tales of Caryll Houselander.

Her Catholic Tales for Boys and Girls (Sophia Press), originally published in the single volume Inside the Ark and Other Stories in 1956, are little gems of stories that are an absolute delight to read. I’ll have to do a separate post that focuses on Houselander and her stories, but for now, allow me to illustrate this idea of truth through fiction by focussing on one of her short stories, “The Uncommunist Cow.”

This was the first story that we read from the volume (my children have a morbid curiosity about communism), and I assumed the author must have had some experience with Soviet communism (she, in fact, fell in love with a Soviet spy).

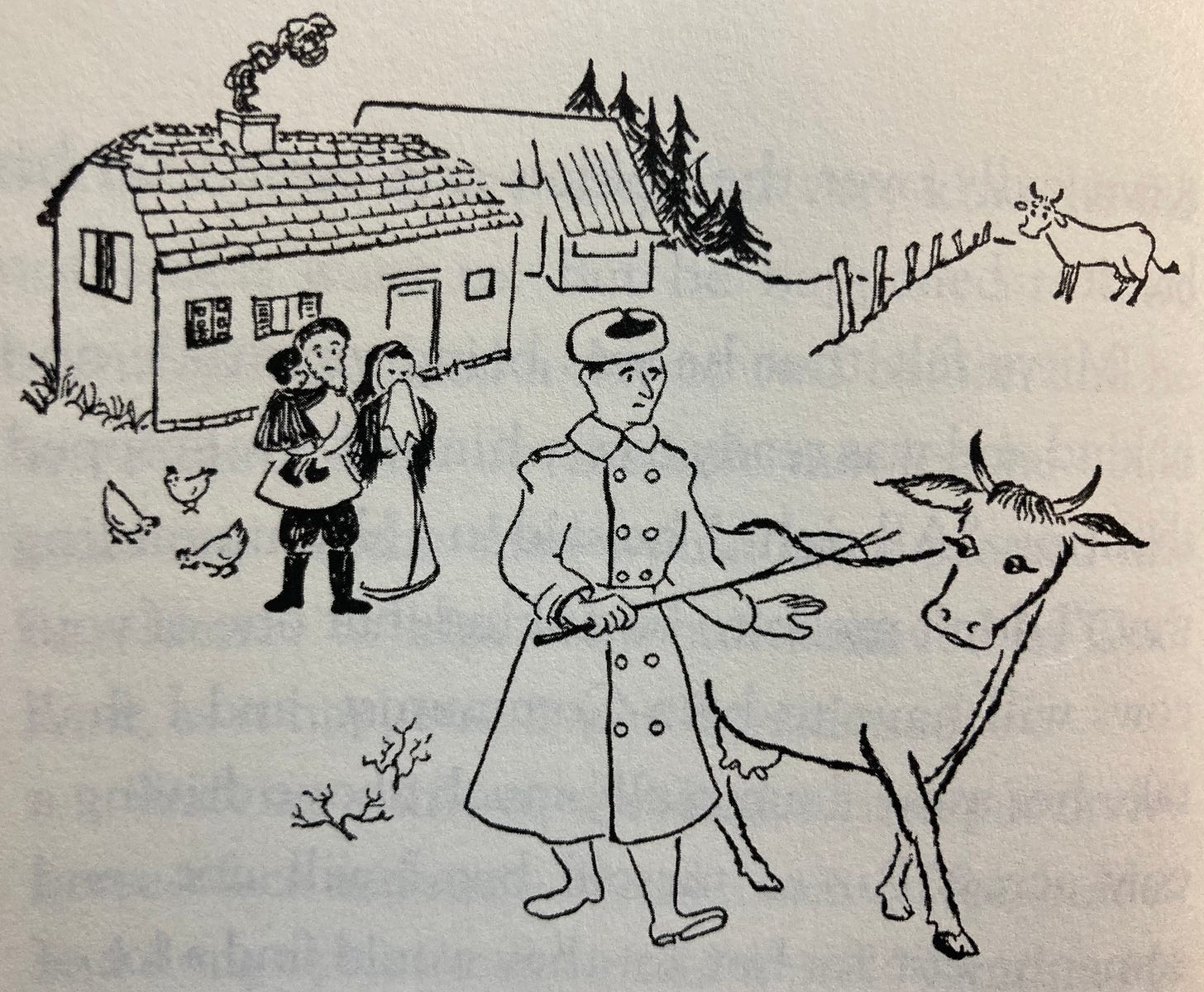

In this story, we learn that it is illegal to have more than one cow, but this family has two cows, twin sisters. Yet they can never go out to the pasture together. They must rotate, so as not to arouse suspicion. The old man Vassilly and the little boy Mischa, his grandson, tend the cows.

Mischa’s parents had brought him to live with his grandparents because his father was conscripted into the Red Army and his mother had to work in the factory. The state orphanage, his father said, would perhaps provide for his material needs better, but “he would not have a real little Russian home. Here he will have everything that makes it sweet to be alive in this darling world. And after this world, Heaven.”

We learn about this family’s priorities. Not only do they keep two cows despite the law, they are also Christians against the law. Despite their privations, the family uses what little money they have to ensure that they always have oil for the lamps that illuminate the icon of our Lady and the Christ Child,

“a very beautiful picture in bright colors and covered, except for the faced, with metal worked all over in flowers and tendrils and leaves and sheaves of corn and sheep and angels and holy words in Russian letters. In front of it a row of tiny green lamps was always burning. Green is the Russian’s color for life . . .”

Concrete details such as this are the mark of a good story, for children and adults. So many modern stories forgo the concrete in favor of abstract dreaminess, believing that to elevate children to a higher reality we must transport them on a cloud of abstractions. In fact, the opposite is true. Here we have a textured description of a tiny corner of a single house of an ordinary family in Russia. It is set in a particular time, in a particular place. This very particularity is what, paradoxically, connects the reader to the universal.

We learn that one day, a “nervous little government official” named Mitya discovers that the family has two cows. Mitya had grown up without a mother or father in a state orphanage. He had never amounted to much and had done anything to please the government, and had never caught anyone breaking Soviet law. But he was “very shy and very kind, and he did not much want to.”

But Mitya felt the need to look bold, so he shouted and gave orders. But as this caused little Mischa to cry, Mitya backed down. “I don’t mean to be unkind, but one of your cows will have to be a Communist,” he said. He told them that he would have to drive her away himself, lest another official come and, doubtless, discover “a lot of things wrong here,” such as the boy not being in an orphanage. The cow, named Natasha, was driven to a crowded state cow orphanage, where she sobbed and longed for home.

Another cow, a Communist cow, reassured poor Natasha that,

“here you enjoy the worldwide sisterhood of cows, and you are sure of your regular food.”

“A worldwide sisterhood isn’t a bit the same as one darling little twin sister in your own sweet, warm home.”

“You are a very unenlightened cow.”

Natasha escaped. The government official caught wind, and knew that if he didn’t rush to retrieve her, another official would, and he might even be sent to prison.

Mitya followed Natasha’s tracks in the snow, and after a long, cold journey, he arrived at the little home. When he “saw the glow of the fire in the kitchen window like a welcome in a world of cold white loneliness, he could not keep down a feeling of longing.”

It was Christmas night, and the family had left their feast to welcome Natasha with tears and kisses of joy.

“So when Mitya opened the house door, no one was there. Yet he was greeted, really greeted, by a sight such as he had never seen before; the poor man’s table laden with festive fare: a chicken, browned and sizzling in the dish, a bowl of white potatoes steaming by it, a new crisp loaf of home-baked bread, dishes of sugared fruits . . . a small Christmas tree . . . the icon lamps were all filled with new oil and burning brightly with the green fire of life. And the table itself was lit by candles, so that the room seemed full of stars.”

When the family walked in and saw him, Mitya threatened arrest. But Old Vassilly convinced him to stay and enjoy Christmas with them, lest they all perish in the snow on a night journey back. In the morning, Vassily said, “we will go where you wish.”

Mitya saw, for the first time, the person of Christ in this little family. He was welcomed as their own child and as the child of God and son of the Virgin, “and the Child Jesus your little Brother,” Babooshka assured him. He celebrated the feast, and stood before the icon when the family did. In the morning, Vassilly made good on his promise and said that they were ready to go with him to be arrested, but we knew this could not be. I will let you savor the end of the story yourself!

This fictional story teaches us about the rich, beautiful world of life with Christ, that the worldwide brotherhood of man is nothing as compared to a warm living room with people who love you and a single lighted icon gazing down on you. In this little world, each person matters, and all are under the protection of the divine Savior.

What exactly the small child takes away from this story, no one can be sure. And for each child, something different stands out, and at each subsequent reading, different details will emerge. But in a mysterious way, it shapes the moral imagination even as it delights us anew each time we read.

This story and stories like it, including poetry, song, and all manner of a moral-lyrical education, reveal a reality that is above one’s ordinary self and, in the words of Irving Babbitt, “can be glimpsed, if at all, only through a veil of illusion and is indeed inseparable from the illusion.” This realm of imaginative insight defies rationalization and transcends the intellect because it touches the infinite, which is beyond the false categories of rationality.

Having homeschooled in the early 80’s and 90’s, being a Catholic convert at 19, always a traditional Catholic, and having a degree in comparative

Literature, you are a woman after my own heart. The moral imagination of a child is the key to his heart and soul. I will enjoy hearing more from you!

Brava.

This is a excellent essay on the role of imagination and a life with Christ! I've been teaching Northrop Frye this semester, and he opens up such clarity about the role literature and imagination: “No matter how much experience we may gather in life, we can never in life get the dimension of experience that imagination gives us. Only the arts and sciences can do that, and of these, only literature gives us the whole sweep and range of human imagination as it sees itself.”