Yes, Crockett Johnson’s Harold and the Purple Crayon is an icon of our childhood. You had it. I had it. You, like me, probably have a copy on your children’s bookshelf or grandchildren’s.

Who could be so coldhearted as to try to deconstruct in Derridean fashion the classic story of the bald-headed baby with the crayon? Yours truly, of course. Leave it to me, as my husband put it, to risk losing of all those newly won, hard-earned paid subscribers (there aren’t many of you, but I very much value you, which is why this must be done) by taking on this piece of Americana.

It is time. It is past time. For the author of this book, which I discovered only after deciding that I hated the book and it needed to be shelved in my infamous (to my children) “banned books library” in our master closet, was a Communist.

That is correct, the author of the children’s book that we could all agree on was in fact working to subvert the U. S. government while editing a magazine that lauded the Soviets as heroes. But more on that later.

Let’s start with the story because that is what tipped me off that there was something off about the imagination of the author.

What’s wrong with a kid carrying a crayon and drawing his world around him?

Behind this premise is an entire set of political and philosophical-anthropological assumptions. The child is, first, alone. He is not even “in the world,” because he himself is the creator of the world, we learn. He starts with a sort of inversion God’s ‘let there be light’: he draws the moon, so that he has light to walk in the darkness. Then he draws the ground, then trees, then creatures (beginning with a frightening dragon). He haphazardly winds up drawing water as his hand shakes the crayon for fear of the dragon.

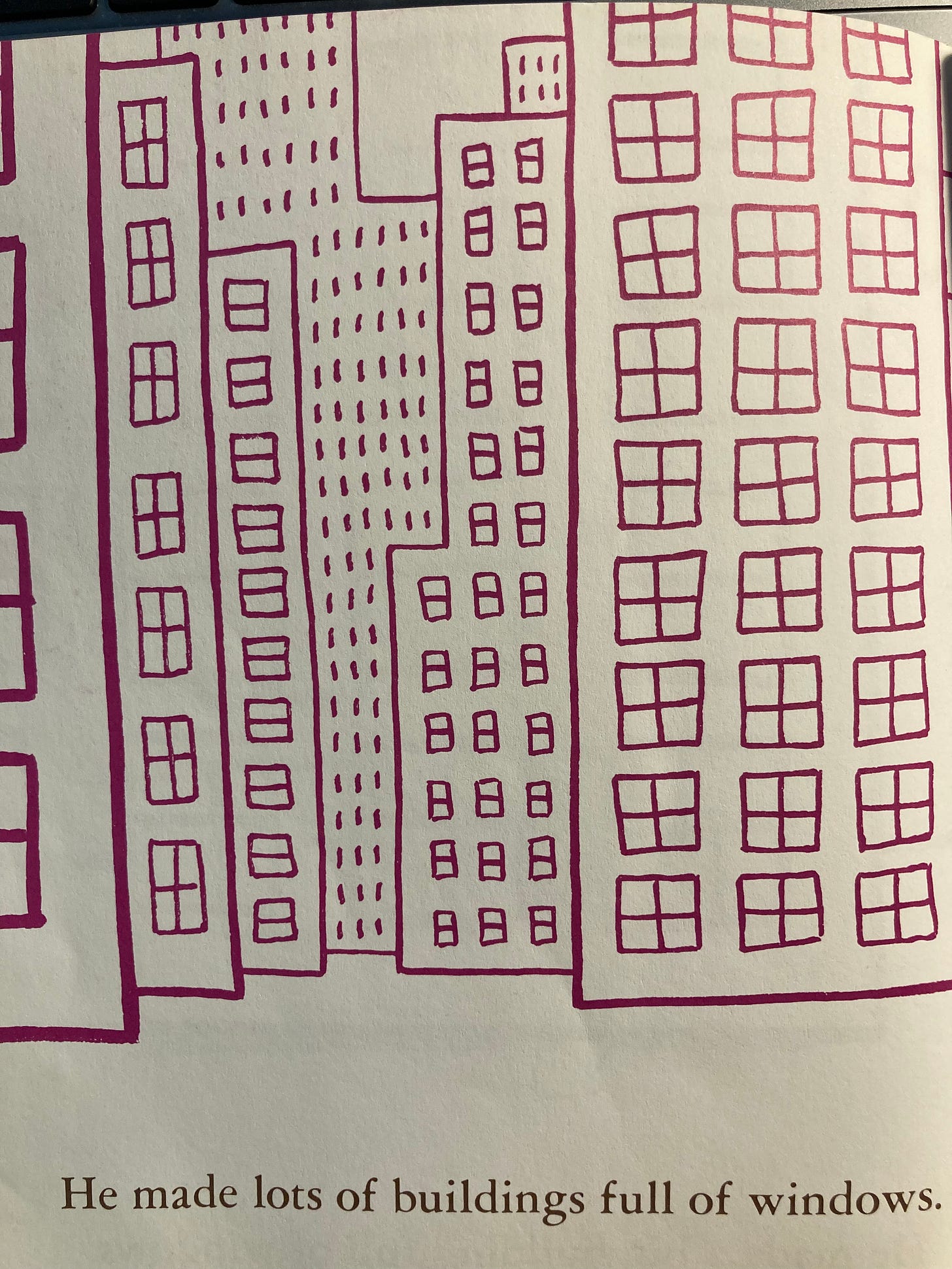

He sails in a boat until he decides to draw a beach. Then he draws his picnic of nine pies. He drifts in a balloon and lands in the yard of a house he drew. But Harold discovers that it is not his house and so he draws many, many windows until, in searching for his house, he has drawn the skyscrapers of a city.

The story ends when Harold realizes that his window was always right around the moon, so he draws it, draws his bed, and draws up the covers. Off to sleep he goes.

Harold and the Purple Crayon puts forth an image of a child, alone in a world that is entirely his own invention. The world, as he invents it, is a tabula rasa, a blank slate awaiting his creative genius. It tickles the imaginations of children because it puts before their eyes the amazing prospect of inventing the world.

Harold is as a god.

Is it any coincidence that the author of this story imagined that the world was at the brink of a New Heaven and New Earth that was to be communism? The communists imagined themselves to be as gods.

But the idea that humanity and the political world are or can be blank slates is not the original invention of communism. This idea can be found in the political philosophy of that great founder of liberalism, John Locke. Locke and other social contract thinkers such as Thomas Hobbes and Jean-Jacques Rousseau revolutionized the West’s understanding of politics from one that was a ground-up operation (Aristotle and Aquinas) to one that is top-down. Karl Marx only built on this rationalistic-romantic foundation.

It is not difficult to see the Marxist influence on the imagination of the author of Harold and the Purple Crayon. The plot of this book operates from the distinctly modern view that politics springs from the head of man in a rationalistic enterprise (recall Harold drawing first the household and then the city—his political act). As for man himself, he is his own uncreated being, entirely at liberty to follow his whims and desires and to fashion the world around him.

The idea of the godlike child, at the center of the universe, and dictating to the world his terms, is at the heart of very many modern children’s books. The minimalist aesthetic and brutalist quality of the city Harold draws seems to be distinctly communist in flavoring (or, alternatively, the way a city would look if a child drew it, if you didn’t know that the author was a communist my husband pointed out). But overall this book is a product of modern romantic and abstract thinking.

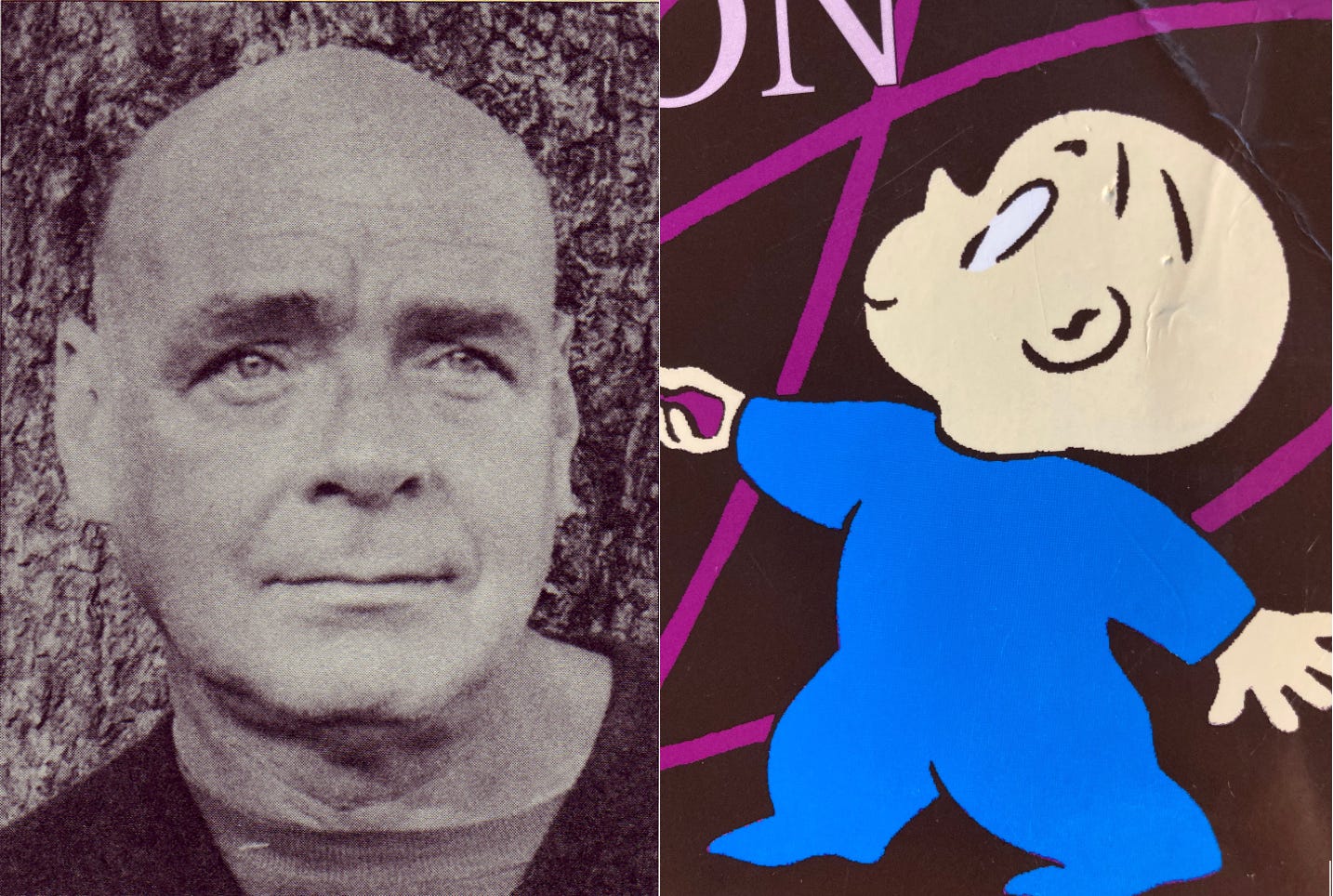

Crockett Johnson began his career as an illustrator by drawing cartoons for the communist publication New Masses. He later became its art editor.

Whittaker Chambers, the famous communist defector and author of the fantastic memoir Witness, also worked for New Masses for a time. Johnson, however, never defected.

Johnson’s second wife was Ruth Krauss, with whom he collaborated on some children’s stories. Interestingly, Krauss collaborated with illustrator and author Maurice Sendak of Where the Wild Things Are fame (see my analysis of that here). These two were so influential that, according to Philip Nel, author of Crockett Johnson and Ruth Krauss: How an Unlikely Couple Found Love, Dodged the FBI, and Transformed Children’s Literature, they inspired many imitators.

They brought into the main a new genre: “outspoken children facing the world on their own terms.”

Some imitators, according to Nel, missed the point and gave us books that “sentimentalized the unruly Krauss-Sendak child character”:

But did this imitator miss the mark entirely? If you’ve been reading this Substack for a bit, then you know how often I warn against romantic excesses and especially in the form of imaginative depictions for children. The bold child going it alone against the world is one offshoot of the romantic mind (à la Rousseau and his Emile) but another is that impressionistic and idealistic sentimentalism of the sort pictured above. “Love is a special way of feeling” just about nails the idea.

Nel says, “fortunately, better artists understood and embraced that vital, rebellious spirit of the Krauss-Sendak books.” Lane Smith is one such author that Nel cites.

If I were to delve into an intellectual history of the élan vital of the rebellious child in children’s literature, I would say that Kobi Yamata’s recent books represent its crowning achievement (see my post on that one here).

One could argue that Harold and the Purple Crayon is not about a rebellious child but one who is “artistic” and a “creator.” Nay, he isn’t rebellious! This isn’t communist propaganda! It is just about a boy who is making art and shows how children are natural creators and if they are just given the opportunity then they will be able to unleash their imaginations, like they were meant to!

I will grant all of that, but I will add that we must qualify what we mean by creativity. Modern assumptions about what it means to be creative are colored by the Romantic movement that gave birth to the notion of the fully liberated and spontaneous individual. The child (and this is Rousseau) should not be constrained by social norms, religious convention, or traditions that inhibit their spontaneous, individual expression.

While Romanticism was reacting against the deadening effects on art and literature of neoclassicism, its answer generated a new movement that enshrined the wrong kind of creativity, the “creativity” that gave us the works of artist Robert Nava, for example:

Nava, or so the sage ArtReview tells us, intentionally “turned away from the pursuit of technically sound representation.” The irony of Nava’s having taken radical individual expressionism to the extreme is that he seems to have learned this technique, (according to ArtReview’s short biography anyway) from his teachers and professors in art school.

Thus, there must be an orderliness to creativity, or as Peter Viereck put it, a “strict wildness.” We want to encourage creativity in children, but we must do so in a way that roots them in the good, true, and beautiful—which is expressed in religious and cultural traditions at their finest.

Harold and the Purple Crayon represents a particular quality of imagination that glorifies the radical individual and especially the spontaneous child à la Rousseau’s Emile. Ultimately the effect of this abstract and romantic genre is to draw children’s imaginations away from the concrete world of bugs and backyard kingdoms (and also God) and toward a sort of chaotic abstractionism. It is interesting that Crockett Johnson never had children, with either of his wives. Nor did his second wife, Krauss. Unlike Kenneth Grahame or A. A. Milne, Johnson was not writing for his own children and seemed not even to be writing with the imaginations of real children in mind.

There are good reasons aside from Johnson’s communist activities to keep this book out of the literary world of your child.

Sometimes it becomes very clear that I was raised by foreigners. I’ve never even heard of this book. But well done sussing him out as a subversive just by the quality of his work.

Your article made me think that in some way this book must have actually been written for adults, not children. It seems to me to perhaps be part of the movement of infantilization as seen by the explosion of YA lit read by adults and the toys market now being wholly 50% dedicated to adults.

My wife and I just debated this article for an hour this morning. Well done!