Grasshopper on the Road

Part III of a series on the imagination of Arnold Lobel

In Grasshopper on the Road, Arnold Lobel opens up another vista for contemplating the human condition. Where Frog and Toad explore a dynamic between different personalities and Owl at Home peeks into some of life’s troubling aspects, Grasshopper on the Road penetrates the political.

The likable and sage character Grasshopper decides to embark on adventure, following a road “wherever it goes.” He encounters some eccentric personalities along the way, giving children a glimpse of what life in society and community might have in store.

The thematic thread that seems to connect all of the stories in this little volume is the perspectival nature of life; there are two sides to the story, but it is important to be discerning and to see the blind-spots of others and ourselves. Surrounding Grasshopper are all sorts of unbalanced personalities, from the fanatical beetles to the bureaucratic mosquito, yet Grasshopper is wise and centered. He is adventurous yet also grounded. He is something of a six-legged Aristotelian spoudaios, serious and full of understanding.

Grasshopper’s character shows us that he is one to trust, and in this way Lobel subtly shows children what is untrustworthy about the extreme personality types that Grasshopper encounters.

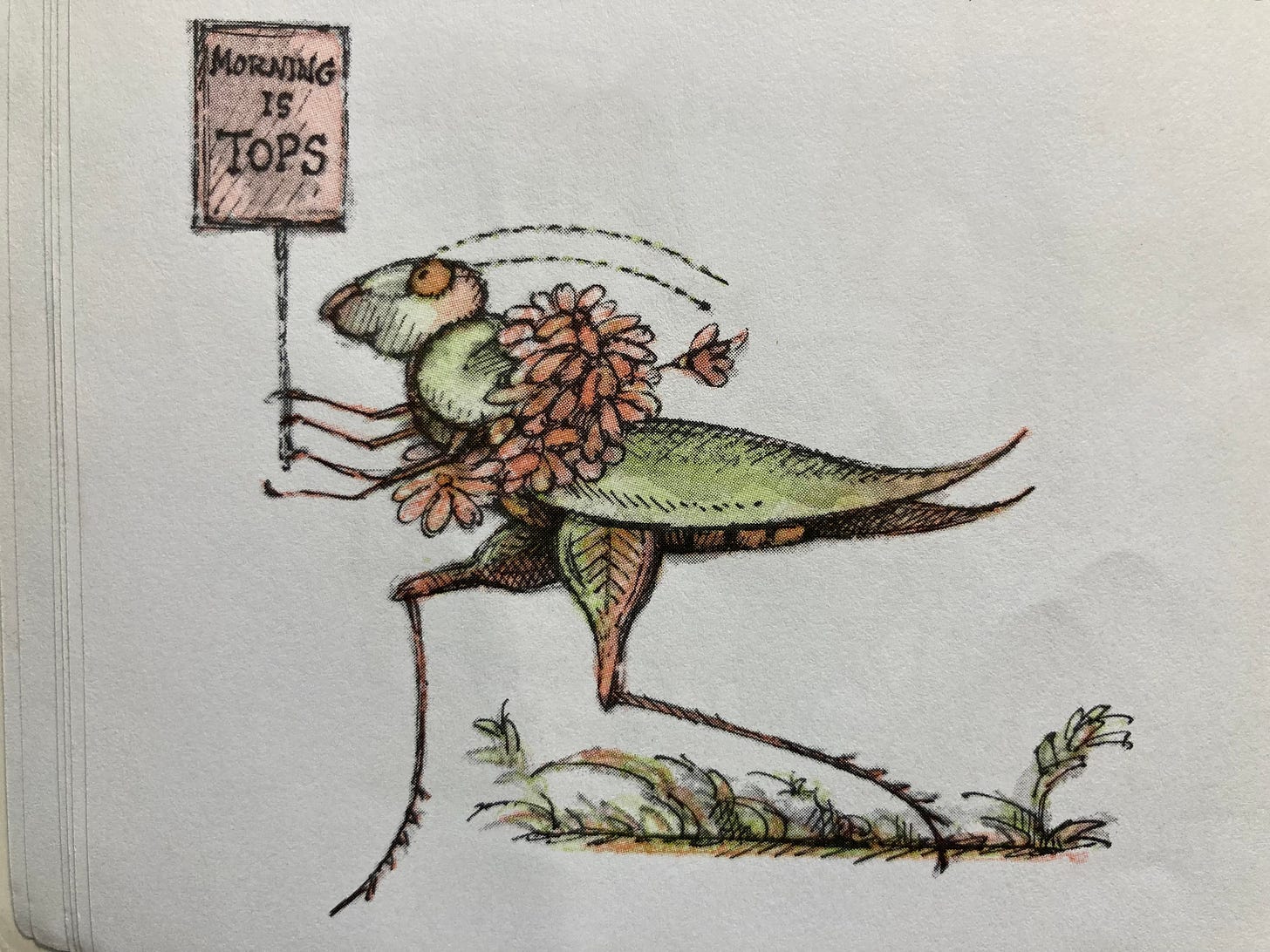

“The Club” begins Grasshopper’s adventure. In this story, Grasshoppers happens upon a sign posted on a tree that says, “MORNING IS BEST.” Then he spots another sign, “THREE CHEERS FOR MORNING.” He soon discovers a group of beetles singing and dancing and carrying signs declaring their love of morning.

He makes the mistake of greeting them with “good morning.” “It is a good morning,” they reply and proceed to tell him about how every day they get together to celebrate morning. When Grasshopper responds that he, too, enjoys morning, they hoist him up on their shoulders, cheer for him, and outfit him with a wreath of flowers.

All is well until Grasshopper commits the faux pas of declaring, “I love afternoon too,” and then, “And night is very nice.” The beetles stop in their tracks.

“Stupid,” said a beetle.

He grabbed the wreath of flowers.

“Dummy,” said another beetle.

He snatched the sign from Grasshopper.

‘Anyone who loves afternoon and night

can never, never be in our club!” said a third beetle.

The beetles grab their signs and march away. Grasshopper “saw the yellow sunshine. He saw the dew sparkling on the clover. And he went on down the road.”

My children especially love the naughty words that the fanatical beetles throw at Grasshopper. The effect is that the children immediately know that the beetles are bad and “crazy,” according to one child, and that Grasshopper is the well-adjusted one in the scene.

Lobel contrasts Grasshopper noticing the beauty of nature (specifically nature in the morning with fresh dew) with the delusional beetles who, although declaring the greatness of morning, miss its real beauty. Their myopia for morning as a mere idea or construct causes them to be blind to the reason that it is lovable.

This story meditates on the universal and the particular. If, like Grasshopper, the beetles were able to appreciate the real worth of morning as an experience of beauty, they would also have to appreciate afternoon and night, too. The particular beauty of morning points beyond itself to beauty that is universal. Grasshopper has this more cosmopolitan or universal perspective—and thus, he earns our trust from the outset.

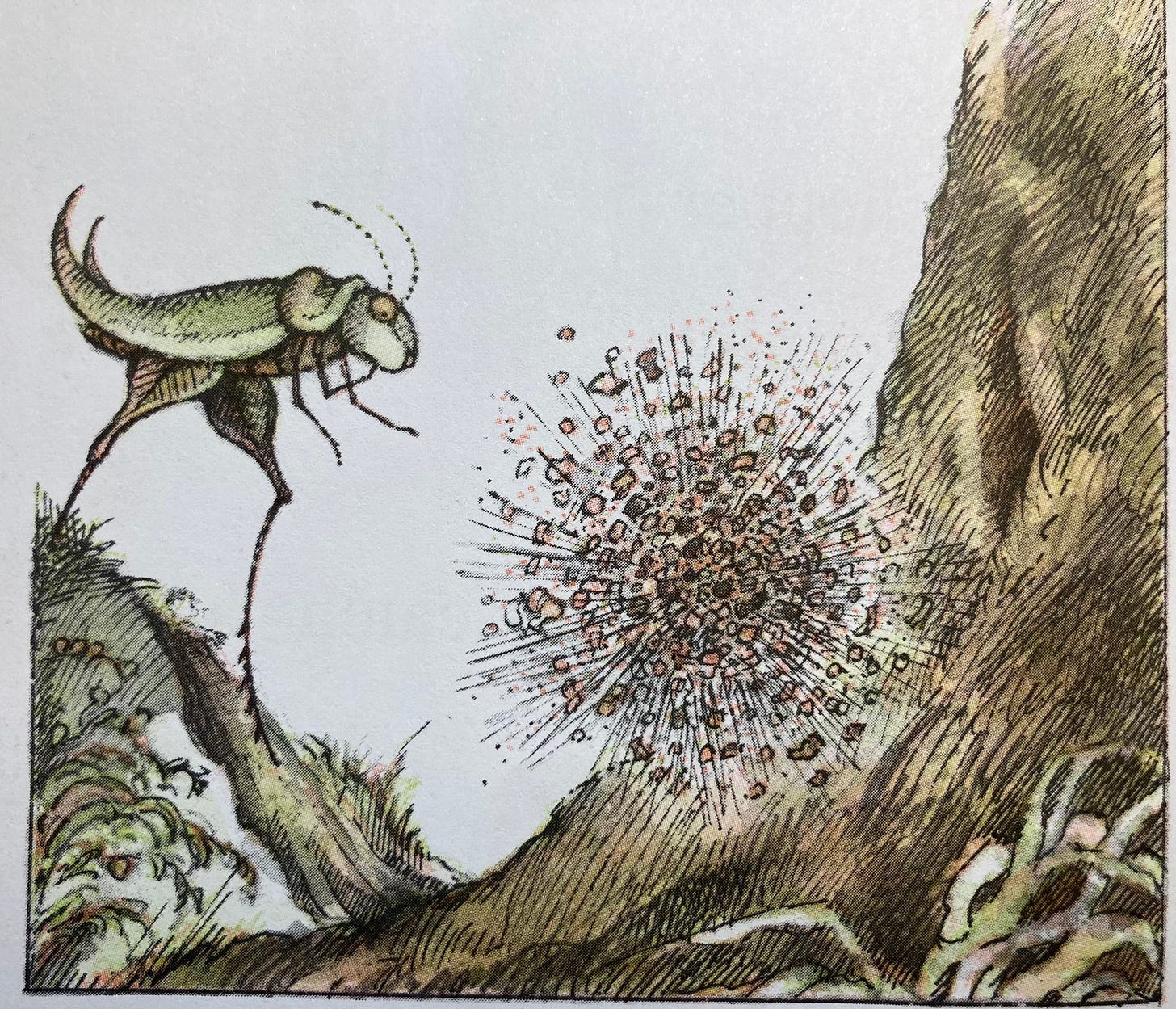

The next story, “A New House,” explores the themes of neighborliness and fortitude. An unwitting Grasshopper takes a bite out of an apple that he found lying on the ground and that happened to be the house of a worm. Suddenly the worm pops out and chides Grasshopper for ruining his home. “You have made a hole in my roof!” he shouts. “It is not polite to eat a person’s house.”

The humor of the scene allows children to see the innocence of Grasshopper’s actions and also the perspective of the worm, whose house was eaten.

The apple begins to roll down the hill, further damaging everything in the poor worm’s house. “My bathtub is in the living room. My bed is in the kitchen!” The kids love it.

Grasshopper runs after the apple and keeps after it all the way down the hill. What is neighborly if not running after that poor worm and his apple?

Grasshopper states the obvious after the worm’s apple-house is obliterated: “‘Too bad, worm,’ said Grasshopper. ‘Your house is gone.’”

The worm, with admirable pluck, decides that, after all, his house was old and, with a big bite in it, it was a fine time to find a new house.

In this story, Grasshopper takes responsibility for something that is not truly his fault but is nonetheless the result of his actions. It is a good lesson because, how often are we caught up in something that we didn’t intend but still must deal with? In family life, this happens often. It’s a good time to show children that talk of “rights” and what’s “fair” is futile. That is not how Christian life works. We must take responsibility for our actions and for our neighbor when he is in need. The beauty of this story is that it conveys this lesson aesthetically, without the need to spell it out in any way. Even if children don’t “get it” the way that we might, it reaches them on another level.

I’ve already covered the great lesson in government that is “The Voyage” in this volume. Once again, my eldest and I had the pleasure of laughing about the mosquito-like experience of TSA at the LAX airport. “Rules are rules” we joked.

The final two stories, “Always” and “At Evening,” again meditate on the nature of perspective. The three butterflies in “Always” are creatures of habit, always repeating the same routine every day. Grasshopper does not say much in this story, mostly listening to the comical if boring routines of the butterflies. In the end, the butterflies declare to Grasshopper that they like talking to him and that they will regale him with their daily routines of scratching and flying, napping and dreaming.

“No,” says Grasshopper. “I am sorry, but I will not be here. I will be moving on. I will be doing new things.”

Grasshopper senses that routine to the point of stultification is not a good thing, even if it seems comfortable. The life of the butterflies is boring because no novelty is ever introduced.

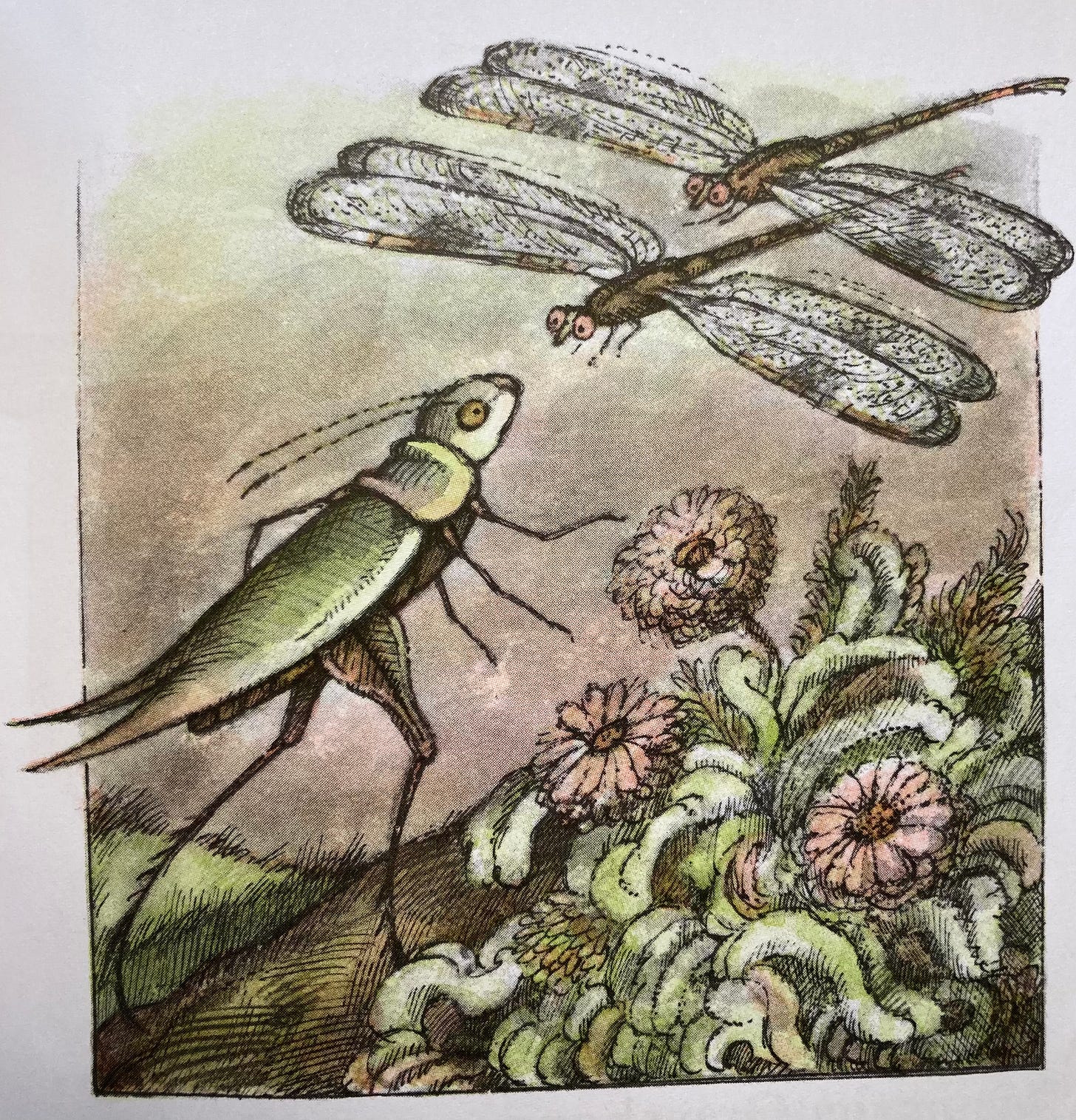

But thrill for the pure sake of thrill is not good either, and this is the final lesson that Lobel illustrates. In “At Evening” Lobel suggests that, although a rolling stone gathers no moss, it is still good to be able to stop and smell the roses. It is evening, and as Grasshopper is walking along the road, suddenly two dragonflies zoom by him. They look down from their height and declare, “Poor Grasshopper . . . We are flying fast. You are only walking. That is very sad.”

“It is not sad,” says Grasshopper. “I like to walk.” Grasshopper says that he enjoys his road and seeing the flowers growing alongside it.

The dragonflies declare that that they are “zipping and zooming” and that they “do not have time to look at flowers.”

Like a good Charlotte Mason student, Grasshopper enjoys observing the leaves moving in the trees and the sunset over the mountains. The dragonflies eventually fly away after saying that they have no time for such things.

The final story is a nice reminder to us parents to make time to see the little things and to appreciate God’s creation from the perspective of those little people. Like Grasshopper, children enjoy the journey and all of the little things along the way. Time moves more slowly for them. They aren’t hurrying to get somewhere, and sometimes we shouldn’t be either.

In this wonderful volume, Lobel illustrates the virtue of spontaneity guided by sound character. Grasshopper is no romantic, idle dreamer. He is out for adventure, but he is not seduced by extremes. He does not need to follow the morning-lovers to learn a lesson that he seems already to know, the myopia of fanatics causes them to miss much of life. Nor does Grasshopper desire to sit idly with the butterflies who are afraid of anything new. Yet at the same time, Grasshopper is able to appreciate the ordinary beauty that is before him—something old that is always new.

Wonderful, Mrs. Finley, just wonderful. Congratulations!

Beautiful reflection. Anthropomorphizing the creatures of the natural world is a marvel of human imagination and engages all minds that are open to it. When we began homeschooling 40 years ago, the local community included parents who didn’t allow their children to read stories where “animals talked”. We thought differently, of course.